Ballet-féerie in two acts and three scenes

Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Libretto by Ivan Vsevolozhsky and Marius Petipa

Décors by Konstantin Ivanov and Mikhail Bocharov

Costumes by Ivan Vsevolozhsky

World Première

18th December [O.S. 6th December] 1892

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg

Original 1892 Cast

The Sugar Plum Fairy

Antonietta Dell’Era

Prince Coqueluche

Pavel Gerdt

Clara

Stanislava Belinskaya

The Nutcracker-Prince

Sergei Legat

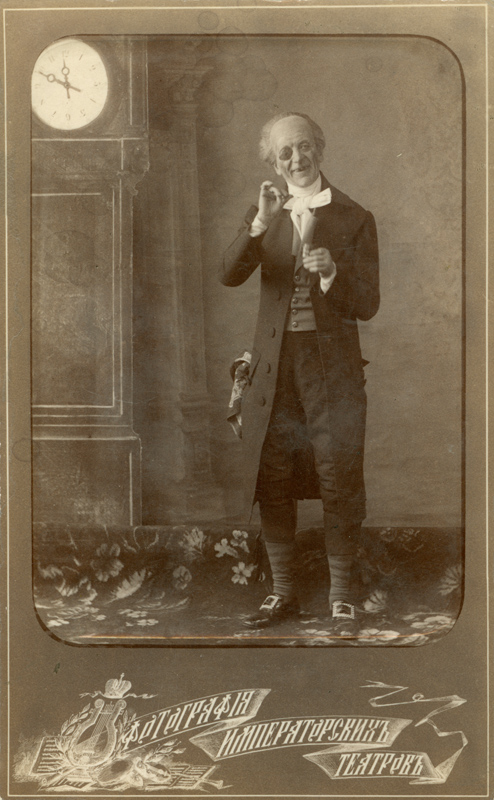

Herr Drosselmeyer

Timofei Stulkolkin

Act 1

President Silberhaus

Felix Kschessinsky

Fritz

Vasily Stulkolkin

Marianne

Lydia Rubtsova

Dolls

The Soldier

Sergei Litavkin

The Sutler

Maria Anderson

Harlequin

Georgy Kyaksht

Columbine

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

Act 2

Grand divertissements

Spanish Hot Chocolate

Marie Petipa

Sergey Lukyanov

Arabian Coffee

Nadezhda Petipa

Chinese Tea

Maria Anderson

Alexander Gorsky

Russian Candy Cane

Alexander Shiryaev

Mother Ginger

Nikolai Yakovlev

Flowers

Anna Johansson

Claudia Kulichevskaya

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

Varvara Rhykhlyakova

Plot

On Christmas Eve, young Clara Silberhaus receives a Nutcracker doll from her godfather Herr Drosselmeyer, but there is more to this doll than meets the eye. That very same night, an army of the mice, led by the evil seven-headed Mouse King invade Clara’s parlour and the Nutcracker and the other dolls miraculously spring to life to fight off the rodents. The dolls are victorious when Clara intercedes, hitting the Mouse King with her slipper. The Nutcracker kills his enemy and the defeated mice disappear. The Nutcracker transforms into a prince and takes Clara on a journey to the magical world of Confituremburg, the Land of Sweets, where they meet the Sugar Plum Fairy and her cavalier, Prince Coqueluche. In thanks to Clara for saving the Nutcracker-Prince, a celebration of dancing sweets and flowers is held and Clara and the Nutcracker are crowned as the new King and Queen of Confituremburg.

History

The Nutcracker was the third and final ballet to be composed by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky and was the second collaboration between the composer, Petipa and Ivan Vsevolovzhsky. Today, The Nutcracker is perhaps the most popular ballet in the world, but the nature of events during its creation and its première were not what one would expect from such a famous and popular ballet. After the success of The Sleeping Beauty, Tchaikovsky received his next commission from Vsevolovzhsky to compose a new one-act opera and two-act ballet, the latter of which was to be based on another children’s tale. It was decided that the opera would be Iolanta, based on the Danish play King Réné’s Daughter by Henrik Hertz, and the ballet would be The Nutcracker, based on the story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King by E.T.A Hoffmann, by way of Alexandre Dumas’s adapted abridgement The Tale of the Nutcracker.

Origins of inspiration

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Nutcracker and the Mouse King was published in 1816 in Berlin in a volume entitled Kinder-Mährchen, Children’s Stories. It tells the story of seven-year-old Marie Stahlbaum, who, on Christmas Eve, receives a nutcracker doll from her godfather, Drosselmeyer, a clockmaker and inventor. However, that night, an army of mice, led by the seven-headed Mouse King invade the parlour and the dolls come to life, with the Nutcracker taking command. Marie, who has snuck downstairs to check on the Nutcracker, comes to his aid by throwing her slipper at the Mouse King. The next morning, she tells her parents everything that happened, but they don’t believe her. Several days later, Drosselmeyer tells Marie the story of Princess Pirlipat and Madam Mouserinks, known as Queen of the Mice. The Mouse Queen tricked a queen into letting her and her children eat the lard that was meant for the King. Enraged, the King set traps for the Mouse Queen and her children, and all the Mouse Queen’s children were killed. The Mouse Queen sought revenge and magically turned Pirlipat ugly. Drosselmeyer was tasked with finding a cure and he and his nephew discovered that Pirlipat had to eat the Crackatook, the world’s hardest nut, and searched everywhere until they successfully found it. Many men tried to crack the nut open, but only Drosselmeyer’s nephew succeeded and Pirlipat ate it and became beautiful again. However, Drosselmeyer’s nephew accidentally stood on the Mouse Queen and was transformed into a nutcracker. The selfish Pirlipat subsequently rejected him as as suitor and banished him from the castle. Marie is taunted by the Mouse King and the Nutcracker asks her for a sword, which she gets from one of her brother Fritz’s hussars. The Mouse King is slayed, the Nutcracker presents his seven crowns to Marie and takes her to the Doll Kingdom where she sees wonderful things. The next day, Marie swears the Nutcracker that she would never behave like Princess Pirlipat and that she would love him no matter what he looked like. There is a bang and her mother comes in to tell her that Drosselmeyer’s nephew has arrived from Nuremburg. By swearing to love him, Marie has broken the curse and made him human again. He asks her to marry him and she accepts him. In a year and a day, he comes back for her and takes her away to the Doll Kingdom, where she is crowned queen.

Composition

When he was given the commission, Tchaikovsky was not very enthusiastic about composing a ballet version of The Nutcracker because the subject did not please him much. Shortly afterwards, a serious rift soon developed between him and Vsevolovzhsky when the latter removed Tchaikovsky’s opera The Queen of Spades from the Imperial Theatre repertoire. Tchaikovsky took great offence to this action and believed that the reason for it was due to his reluctance to participate in the creations of The Nutcracker and Iolanta and even suspected that his work was not appreciated by the Tsar, himself. Vsevolozhsky, however, explained that the reason for the removal of The Queen of Spades was due to casting and scheduling, and went onto point out Tchaikovsky’ reluctance to accept the praise of the Tsar for him at the opera’s dress rehearsal. With this, the rift between the composer and the director was settled and by 25th February [O.S. 13th February] 1891, Tchaikovsky had started to compose the music for the new ballet. Petipa was commissioned as choreographer and, like he had done with The Sleeping Beauty, gave Tchaikovsky a list of instructions for the music. By 6th March [O.S. 22nd February], the day he left Saint Petersburg for a tour of Paris and America, Tchaikovsky had drafted the music for half of the first act and the Waltz of the Snowflakes. But the problems were far from over.

Tchaikovsky continued to compose the music for The Nutcracker and Iolanta while he was touring, but the experience caused him great emotional distress and he was not satisfied with the resulting music he had composed. He wrote to Vsevolozhsky requesting for the new opera and ballet’s premières to be postponed until the 1892-93 season. Then, on the 16th April [O.S. 4th April], Tchaikovsky learned the devastating news that his sister Alexandra had died and Vsevolozhsky respectfully granted Tchaikovsky’s request to postpone The Nutcracker and Iolanta until the next season while the composer went into mourning for his dear sister. The score for The Nutcracker was finally completed when Tchaikovsky had returned to Frolovskoe, but more problems still arose, this time in relation to the story, which the collaborators came to realise was not entirely suitable for adaptation into ballet. The libretto, which differed in some details from Tchaikovsky’s instructions and Petipa’s plan, proved to be quaint and was very different from Hoffmann’s original story. The dark tone had been completely watered down, not in the least because of the omission of the backstory of Queen Mouse and Princess Pirlipat. The libretto’s most problematic defect was that it was made up of an action-filled first act, which was followed by an almost static second act that was almost entirely a Grand divertissement. Perhaps the most problematic defect was that the two acts were combined by a very abrupt merging of the everyday and fantasy worlds, something which Hoffmann had taken great pains to create in his original story and something that Petipa had smoothly provided in The Sleeping Beauty and would again in Swan Lake. In short, many felt that this libretto did not offer much promise for good theatre. The result was a simple children’s tale without any significance or any moral. It was perhaps the ultimate ballet spectacle.

When work and planning finally began on the choreography, Petipa went beyond tradition by casting children in the roles of Clara, Fritz and the Nutcracker. The original Clara was the 12 year old Stanislava Belinskaya and the original Nutcracker-Prince was the 17 year old Sergei Legat. Children in classical ballet productions was nothing new since Petipa had included children’s dances and small corps de ballets of children in almost all of his ballets. The main reason why students of the Imperial Ballet School obtained early roles on the Imperial Theatre stage, according to the critic Sergei Khudekov, was because “Children’s dances were loved in the highest circles.” However, the children’s lack of technical attainments meant that Petipa was refrained from choreographing difficult dances for them. These dances were reserved for the adults, who were cast in the roles of the story’s secondary characters.

After such a rocky start to the ballet’s creation, rehearsals for The Nutcracker finally began, but in August 1892, Petipa withdrew as choreographer when he fell ill and had to take leave for the rest of the 1892/93 season. In the aftermath, Vsevolozhsky temporarily appointed Petipa’s assistant Lev Ivanov as Ballet Master during Petipa’s absence and commissioned him to take charge of choreographing The Nutcracker. Enrico Cecchetti was appointed second ballet master to Ivanov. It is unknown if Petipa managed to choreograph any steps and sequences for the ballet before his withdrawal, but it is certain that he had a hand in the libretto and the stage direction.

World première

The Nutcracker premièred in a joint performance with Iolanta on the 18th December [O.S. 6th December] 1892 at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, with the Italian Prima Ballerina Antonietta Dell’Era as the Sugar Plum Fairy, Pavel Gerdt as Prince Coqueluche, Stanislava Belinskaya as Clara and Sergei Legat as the Nutcracker-Prince. The ballet, however, was not met with an enthusiastic response, with many criticising the flaws of the libretto and the mixed spectacle of opera and ballet. Many felt that the transition from the real world to the magical world in the first act was “too abrupt” and others criticised the fact that they had to wait until after midnight for the Prima Ballerina to perform since she only performed in the second act. Alexandre Benois described the choreography in the battle scene as confusing, writing in his memoirs: “One cannot understand anything. Disorderly pushing about from corner to corner and running backwards and forwards – quite amateurish.” There were, however, some mixed reactions to certain features in the ballet, most notably the performance of Olga Preobrazhenskaya as Columbine in the first act – some called her performance “insipid”, while others called it “nice”. There was praise for some features, for example, Maria Anderson’s performance as Chinese Tea was praised and perhaps the most successful number of the whole ballet was the Waltz of the Snowflakes. Nevertheless, The Nutcracker certainly did not meet the same level of success as The Sleeping Beauty. Many dismissed it as too grand a spectacle that lacked serious storytelling and a subject to even be considered a ballet, as explained by the following review:

First of all The Nutcracker can in no event be called a ballet. It does not comply with even one of the demands made of a ballet. Ballet, as a basic genre of art, is mimed drama and consequently must contain all the elements of norm drama. On the other hand, there must be a place in ballet for plastic attitudes and dances, made up of the entire essence of classical choreography. There is nothing of this in Nutcracker. There is not even a subject… – Birzhevye vedomosti (8 Dec 1892), p. 2

However, reception towards Tchaikovsky’s music was better and the score proved to be a success in its own right. Before the ballet’s première and after the score was completed, Tchaikovsky had selected eight numbers and arranged them for his Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a, intended for concert performance. The Nutcracker Suite premièred on the 19th March [O.S. 7th March] 1892 at an assembly of the Saint Petersburg branch of the Musical Society and was a huge success. When the ballet premièred, critics found it necessary to review Tchaikovsky’s music as a separate entity from everything else:

… it is a pity that so much fine music is expended on nonsense unworthy of attention, but the music in general is excellent: that designated for dances is dansante and that designated for the ear and for the fantasy is imaginative. Of Tchaikovsky’s three ballets… ‘Nutcracker’ is the best, its music indeed not for the normal ballet audience. – Peterburgskaya gazeta (9 Dec 1892), p. 4

Despite the mixed to negative reception it received at the première, The Nutcracker remained in the Imperial Ballet repertoire for at least one more season, but from approximately 1894-95, it was no longer active in the repertoire. The ballet remained absent for at five years before it was revived in 1900 by Ivanov. After its revival, The Nutcracker remained in the Imperial Ballet repertoire and was performed for the final time in Russia on the 25th October 1917.

The Nutcracker was notated in the Stepanov notation method in 1909, while the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy was danced by Olga Preobrazhenskaya, and is part of the Sergeyev Collection.

The Nutcracker in the 20th Century

Throughout the 20th century, The Nutcracker went through countless revivals and restagings in the hands of various choreographers.

In 1919, Alexander Gorsky staged his own revival of The Nutcracker for the former Imperial Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow and it was in this production that many of the ballet’s most famous modern traditions began. Gorsky made Clara and the Nutcracker-Prince roles for adults rather than children and introduced a definitive romantic relationship between the two characters. He omitted the Sugar Plum Fairy and Prince Coqueluche and gave their dances to Clara and the Nutcracker-Prince. These changes were retained by Soviet choreographers, especially by Vasily Vainonen for his 1934 production for the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet and by Yuri Grigorovich for his 1966 production for the Bolshoi Ballet. In these productions, the heroine’s name was changed from Clara to Masha (the Russian diminutive of her original name Marie). Vainonen’s production introduced the epilogue in which Masha (Clara) wakes up back in her house, realising everything was a dream, and the Nutcracker turns out to be just an ordinary doll. Eventually, choreographers outside of Russia picked up these traits from Gorsky’s staging for many western productions.

The Nutcracker in the West

One of the earliest productions of The Nutcracker in the west was staged by Anna Pavlova in 1911 when she presented a new ballet for her company called Snowflakes, which was based on the snowy forest scene and choreographed by Ivan Clustine. For this ballet, Pavlova utilised various music excerpts from the full length score, including The Journey through the Pine Forest and the Waltz of the Snowflakes. This seems to have been the first production to use the music for The Journey as a pas de deux, as Pavlova utilised it as a pas de deux for a Snow King and a Snow Queen. She also used children in her new little ballet as a corps de ballet of snowflakes, while the roles of the Snow Queen and the Snow King were danced by Pavlova and Laurent Novikov. Snowflakes premièred on the 7th August 1911 in London and was met with a very warm reception.

One of the earliest full-length productions of The Nutcracker to be staged in the west was Nikolai Sergeyev’s production, based on his notation scores, for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet that premièred on the 30th January 1934, with Dame Alicia Markova as the Sugar Plum Fairy and Stanley Judson as her Cavalier. The Nutcracker was staged in more revivals in the west and finally, it began to enjoy popularity when George Balanchine choreographed his version for the New York City Ballet in 1954.

Balanchine was very familiar with The Nutcracker and the Imperial Ballet production, having danced in it when he was a student at the Imperial Ballet School; he had danced the role of the Nutcracker-Prince when he was 15 years old. Like with all his productions of the classics, Balanchine based his Nutcracker on the Imperial Ballet production, restoring many of the distinctive features that some productions had since changed, such as casting children in the main roles and Clara’s adventure being real. However, Balanchine’s production did not avoid differences to the Imperial Ballet production. For example, he changed the name of the leading girl from Clara to Marie (her name in Hoffmann’s original story) and portrayed the Nutcracker as being Drosselmeyer’s nephew (like he is in Hoffmann’s story). Balanchine omitted the variation of the Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier and relocated the Variation of the Sugar Plum Fairy to the beginning of the second act. He also changed the ending by having Marie (Clara) and the Nutcracker leave the Land of Sweets and returning home in a sleigh pulled by a flying reindeer. Balanchine’s The Nutcracker premièred on the 2nd February 1954 at New York City Center with Maria Tallchief as the Sugar Plum Fairy, Nicholas Magallanes as the Cavalier, Zina Bethune as Marie and Paul Nickel as the Nutcracker. The production was a huge success and from then on, The Nutcracker became increasingly popular with ballet audiences.

Following the success of Balanchine’s production, The Nutcracker continued to be staged in various productions for the remainder of the 20th century. Some more of the most famous productions that are still danced today include Rudolf Nureyev’s 1963 revival for the Royal Ballet, which he later revived in 1988 for the Paris Opera Ballet. In 1985, Sir Peter Wright staged a new production for the Royal Ballet that was partially inspired by Hoffmann’s original story and the notation scores by Nikolai Sergeyev. In 1990, Wright staged a new production for the Birmingham Royal Ballet that differed quite vastly from his 1985 production. He later revived his Royal Ballet production in 1999, in which he included features from his 1990 production. In 2012, Yuri Burlaka and Vasily Medvedev staged a new revival of The Nutcracker that used the original 1892 décor and costumes for the Staatsballett Berlin that was based on the Imperial Ballet production, but included some of the modern traditions.

The Nutcracker has come a long way since its ill start in 1892 and today, it is perhaps the most popular ballet in the world, with many marking it as a perfect Christmas treat.

Waltz of the Snowflakes

According to those who witnessed the 1892 première, the most successful number of The Nutcracker was the Waltz of the Snowflakes. The idea for this waltz came from The Daughter of the Snows, which had featured a dance number entitled Dance of the Snowflakes. In some modern productions, the Waltz of the Snowflakes features soloist roles, such as Snow Fairies, winds, Snow Kings and Snow Queens and feature dancing for Clara and the Nutcracker-Prince. This, however, is not the case in Ivanov’s scenario, in which it is solely a dance for a huge corps de ballet. The original Waltz of the Snowflakes was performed by over fifty dancers and includes special group patterns that form the effects of a snow fall, which escalates into a blizzard. When the blizzard has passed, the dancers form a tableau vivant at the end, which closes both the dance and the first act.

The ballet critic, Skalkovsky wrote the following statement about the Waltz of the Snowflakes in the original 1892 production:

The downy pompoms on the white dresses, on the headwear in the form of rays of stars, and on the accessories in the form of clusters of wands swaying in the dancers’ hands, very successfully and picturesquely represented the movements of snowflakes, while the initial grouping [of dancers] produced a fine impression of the artistic allegory of a snowdrift – Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta (8 Dec 1892), p. 3

Grand divertissements

The most famous passages from The Nutcracker are the Grand divertissements of the second act, which are perhaps more famous for their music rather than their choreography, since Tchaikovsky’s music for The Nutcracker is a success in its own right. In many modern productions, the scenario for the Grand divertissements has drastically changed, with some productions presenting four of the numbers as standard national dances. In the Imperial Ballet scenario, however, while four of the dances are national dances, in relation to the music at least, they are in fact “dancing sweets” of different nationalities. The dances of the Grand divertissements are Spanish Hot Chocolate, Arabian Coffee, Chinese Tea and Russian Candy Canes and the Dance of the Reed Pipes is performed by Danish Marzipan Shepherdesses. One dance that is often omitted from modern productions is the dance of Mother Ginger and her Polichinelle children. In this number, Mother Ginger enters wearing a huge skirt, from which her Polichinelles emerge and dance.

Perhaps the most interesting of the original “dancing sweets” numbers was the Trepak of Russian Candy Canes. The original version was danced and choreographed by Alexander Shiryaev, though he received no credit for the choreography in the programme, which was not unusual at the time. It was quite common practice for the male dancers to choreograph their own variations and not receive credit for them. The original Trepak was performed by Shiryaev as leading soloist and a corps de ballet of twelve male students. The most interesting feature was the use of hoops by all thirteen dancers and one critic wrote that at one point, Shiryaev “adroitly jumped through a hoop.” Skalkovsky wrote the following, brief account of the Russian Dance and the dance of Mother Ginger:

The dance of the jesters [i.e. the Russian Dance] – by students of the school – serves only as a background for the complicated pas of Mr Shiryaev, who performed his difficult part with striking precision… The dance of the polichinelles – led out by their jolly aunt [mère Gigogne, Mr Yakovlev] – is a copy of the children’s harlequinade composed and produced by balletmaster Petipa during the revival of the ballet ‘The Wilful Wife’ – Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta (8 Dec 1892), p. 3

The Russian Dance is not notated in the Sergeyev Collection, but it was notated by Shiryaev by means of the use of animated stick figures. When George Balanchine choreographed his Nutcracker, he staged Shiryaev’s original Russian Dance, which he, himself, had danced – he had danced one of the children’s roles when he was a student and had later danced the soloist role as an adult to great acclaim. Balanchine kept Shiryaev’s dance almost completely in tact, for he made one minor change in the opening sequence when he replaced Shiryaev’s two grand écartes for a jump in which the dancer has both his knees bent and jumps through his hoop.

One of the most famous numbers of the Grand divertissements is the Waltz of the Flowers. The original 1892 version was danced by twenty-four corps de ballet couples and eight soloists, among whom were Anna Johansson, Claudia Kulichevskaya, Olga Preobrazhenskaya and Varvara Rhykhlyakova and featured a golden vase containing golden flowers raised by the corps de ballet. The flowers represented in the waltz have been changed in countless modern productions, but in the Imperial Ballet production, they were marigolds and for a very personal reason. When Evgenia Petipa died, marigolds suddenly grew in Petipa’s garden, so the flowers represented in the Waltz of the Flowers were marigolds as a tribute to Petipa’s beloved daughter. When The Nutcracker premièred, the Waltz of the Flowers was not met with the same enthusiasm as the Waltz of the Snowflakes and when the ballet was later revived, the waltz underwent several changes. The golden vase was removed and the number of dancers was reduced; the number of dancers in the corps de ballet was reduced from twenty-four to sixteen and the number of soloists was reduced from eight to six. In some modern productions, the soloists in the Waltz of the Flowers are omitted and the number is solely a dance for the corps de ballet. In other productions, the soloists are not flowers and some versions have one leading soloist, with two prime examples being Balanchine’s and Sir Peter Wright’s respective productions. In Balanchine’s staging, the leading soloist is called Dewdrop and Sir Peter Wright’s leading soloist is a Rose Fairy, a role he added to the ballet when he staged his 1990 production. The role was later added to his production for the Royal Ballet in 1999.

The final dance of the Grand divertissements is the Grand Pas de deux, which is performed by the Sugar Plum Fairy and Prince Coqueluche. In some modern productions, however, it is danced by the adult Clara and Nutcracker-Prince. One very interesting feature about the original version of the Grand Pas de deux was the use of a stage trick nicknamed a “reika”, which means river in Russian. In this trick, the Sugar Plum Fairy, supported by Prince Coqueluche, stepped onto a special platform en pointe and began to move from across the stage. The trick gave the illusion that the ballerina was gliding across the stage by magic. This was another feature of the Imperial Ballet production that was retained in Balanchine’s Nutcracker and the “reika” was also used in Sir Peter Wright’s 1985 production for the Royal Ballet. However, the trick has since been removed from his production, but is available to view in the filmed performance from 1985 that is available to purchase on DVD, where it is performed by Lesley Collier and Sir Anthony Dowell. The famous photograph below of Varvara Nikitina and Pavel Gerdt is believed by some to be a depiction of the “reika” moment and if it is, it is suggesting that some sort of tulle shawl was used as part of the trick in 1892. However, this photograph is a studio photograph and there is no mention of a shawl in the notation scores. The notation scores state that the Sugar Plum Fairy balances en arabesque, supported by Prince Colqueluche, just like what is done in Balanchine’s staging. In light of this photograph regarding the original “reika” trick, there are two possible explanations for the shawl – there could have been no shawl at all and was only added to this photograph for effect, or a shawl was originally used in 1892, but was omitted when The Nutcracker was revived in 1900.

Sources

- Wiley, Roland John (1985) Tchaikovsky’s Ballets: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press

- Wiley, Roland John (1997) The Life and Ballets of Lev Ivanov. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.