Ballet pantomime in two acts and four scenes

Music by Adolphe Adam

Libretto by Eugène Desmares

Décor for the 1880 Saint Petersburg production designed by Heinrich Wagner

World Première

21st September 1836

Salle Le Peletier, Paris

Choreography by Filippo Taglioni

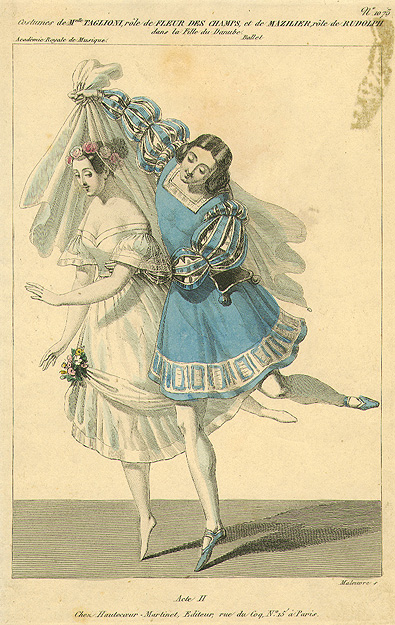

Original 1836 Cast

Fleur des Champs

Marie Taglioni

Rudolph

Joseph Mazilier

The Nymph of the Danube

Amélie Legallois

Saint Petersburg Premiére

1st January 1838 [O.S. 20th December 1837]

Imperial Kamenny Bolshoi Theatre

Original 1837 Cast

Fleur des Champs

Marie Taglioni

Rudolph

Nikolai Goltz

Première of Petipa’s revival

8th March [O.S. 24th February] 1880

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

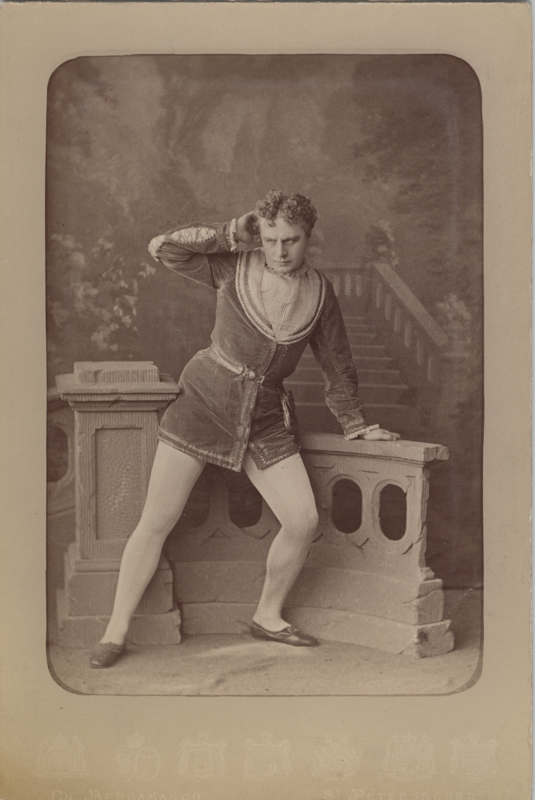

Original 1880 Cast

The Daughter of the Danube

Ekaterina Vazem

Rudolph

Pavel Gerdt

History

After the success of Filippo Taglioni’s La Sylphide in 1832, the career of his daughter Marie was at its peak. That same year, her father created another ballet for her, Natalie, ou La Laitière suisse, a ballet with a different setting than that of La Sylphide as it did not touch on the supernatural. By the end of the year, Marie Taglioni had conquered Paris. Her repertoire continued to grow and in 1836, her father would return to the world of the supernatural to create another new ballet for her. This new work, however, was created during a time when outside of the theatre, Marie’s personal life was going through turmoil. Her unhappy marriage to the Comte Gilbert de Voisins, whom she had married in London in 1832, finally came to an end in 1835, but before long, Marie discovered that she was pregnant and a knee injury put her dancing on hold. She later met and fell in love with a young writer Éugene Desmares and they are said to have become lovers after meeting at a masked ball in January 1836. While Marie awaited the birth of her child and recovered from her knee injury, Desmares wrote the scenario for the new ballet that was to be called La Fille du Danube. After the world première of Jean Coralli’s Le Diable boiteux on the 1st June, Filippo Taglioni was finally able to start working on the choreography and staging of La Fille du Danube and commissioned to compose the music was Adolphe Adam, who, at the time, was a fresh face at the Paris Opéra. Prior to this commission, he had composed over thirty operas in Paris and two ballets in Paris and London. After Marie gave birth to a daughter, she returned to the stage on the 10th August 1836, performing in La Sylphide. For her new role, Marie was to embody another type of supernatural maiden – she had previously embodied the undead as the ghost of Abbess Helena in Ballet of the Nuns and then a maiden of the air when she danced the Sylph. Now, she was to become a maiden of the water – a water nymph.

Origin inspirations

Stories of encounters of maidens of the water and mortal men were commonly found around Europe, with the most famous being Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale The Little Mermaid, published in the same year that La Fille du Danube premièred. In Greek mythology, the famous maidens of the water were the sirens, the Oceanids and Nereids of the sea, and the naiads of the rivers and lakes and were known for being deadly as they would lure mortals into the waters in which they lived and drowned them. For La Fille du Danube, the mythical water maiden that served as the inspiration for the ballet’s plot was the Donauweibchen (the Danube River Nymph), a legendary water maiden who helped fishermen to catch a good catch and warned them of floods; a water maiden much friendlier than many of her fellow European counterparts.

Libretto

The first scene of the first act takes place in the Valley of the Flowers in Austria, through which the River Danube flows. The young and beautiful, but mysterious Fleur-des-Champs lives in a cottage on the Danube riverbank with her adoptive mother Irmengarda. She was discovered as a baby on the riverbank and raised by mortals, but her true identity is that she is the Daughter of the Danube, a water nymph, and watching over her is the Nymph of the Danube. Fleur-des-Champs emerges from the cottage to offer flowers to the Danube, her customary morning prayer. Having received her father’s blessing, she returns to the cottage. The young Rudolph, the equerry of Baron Willibald, arrives to meet Fleur-des-Champs. She re-emerges from the cottage and the two reaffirm their love, with Rudolph placing a garland of forget-me-not flowers on Fleur-des-Champs’ head. The Nymph of the Danube, who has been watching the rendezvous, emerges from her grotto and puts the lovers into a deep sleep. She places a ring on each of their hands and disappears. Rudolph and Fleur-des-Champs awake, thinking they both had a strange dream. They realise that they are now betrothed and embrace in their joy. However, Irmengarda comes out of the cottage and upon seeing the lovers together, she ruthlessly drives Rudolph away because she believes him to be unsuitable as a suitor for her daughter. It is her wish for Fleur-des-Champs to marry someone of wealth and nobility or royalty. Rudolph despairs, but Fleur-des-Champs’s gaze of reassurance comforts him and he departs. As Fleur-des-Champs is about to return to the cottage, some of her friends arrive and beckon her to join in their games. At first, she refuses, but then she gives in and the dance and make merry. Suddenly, trumpets are heard, heralding the arrival of Baron Willibald. He has heard much about the mysterious girl and orders for all the girls of the Valley to be invited to his castle so he can choose one of them to be his wife. Every mother is delighted, but none more so than Irmengarda. Fleur-des Champs, however, is troubled, as is Rudolph, but Fleur-des-Champs consoles him by promising to be as un-charming and unladylike as possible and reminding him of the dream that united them and their nymph-protectress. When all the girls have changed into their finest clothes, Rudolph leads them to the castle.

The second scene takes place in Baron Willibald’s castle. The Baron enters as everyone gathers in the hall, after which, all the girls of the Valley enter. They are all decked in their best clothes, their white dresses adorned with flowers, while Fleur-des-Champs has a garland of nymphae and a bouquet of forget-me-nots. The noblewomen are deeply offended by this idea, but the Baron is pleased and invites the valley girls to join the celebration. Dancing begins and Fleur-des-Champs, keeping her promise to her beloved: sorrow darkens her features and she displays a deliberate clumsiness, much to Irmengarda’s fury, but to Rudolph’s joy. However, Fleur-des-Champs’s efforts prove to be in vain, as, when the dancing is over, Baron Willibald chooses her to be his wife, to the delight her mother and the horror of Rudolph. He offers her all the riches and prosperity he has, but Fleur-des-Champs rejects the Baron’s proposal, despite his begging. Rudolph runs between them, reminding the girl of her love and the Baron of his mercy, but Willibald angrily rebuffs him and takes the girl’s hand. Fleur-des-Champs tears away and runs to a balcony that overhangs the Danube. Everyone is horrified. Fleur-des-Champs expresses her aversion to the marriage and declares her love for Rudolph: she curses the Baron, tosses her bouquet of forget-me-nots to her beloved and throws herself off the balcony into the Danube. Everyone is left in horror and shock, but no one more so than Rudolph, who, in his grief, loses his reason.

Thinking his love to be dead, Rudolph goes mad with grief and just as he is about to throw himself into the river, the spirit of Fleur des Champs suddenly appears, but she vanishes at the approach of the Baron, who tries to restore his equerry’s reason with the help of a girl dressed to resemble Fleur-des-Champs. However, the grief-stricken Rudolph is not fooled and plunges into the Danube. What followed the mad scene was the ballet’s “white act”, which took place in the underwater kingdom of the River Danube. Rudolph finds himself surrounded by water nymphs, led by the Nymph of the Danube, who has long been watching over Fleur des Champs. The water nymphs prove to be different from the wilis, though they still have a deed to carry out; rather than drowning him, they test Rudolph’s love for Fleur des Champs. Cladded in veils, the nymphs attempt to entice Rudolph with their charms, but he repulses them all and recognises his beloved, who is now in water nymph form, among them and swears his love only to her, passing the test. Unlike James and the Sylph, Rudolph and Fleur des Champs are accepted as a couple by both the mortal world and the supernatural world and are allowed to leave the fairyland of the Danube and return to the surface, where their happy ever after awaits them.

World Première

La Fille du Danube had its world première on the 21st September 1836 at the Salle Le Peletier, however, the ballet was not met with the same success as La Sylphide. While diehard Taglioni fan, Jules Janin called the ballet “the sequel to La Sylphide“, other critics dismissed it as “a work of little merit”. The newspaper Moniteur called it “boring and inconsequential nonsense, a jumble of worn-out, commonplace stuff.” Frédéric Soulié of the Presse wrote, “M. Taglioni has never produced anything more commonplace… [He] is following the method of dressmakers and political and literary geniuses by applying the maxim that tells us that there is nothing new but what has been forgotten.” The critics found the plot dull and boring and it was only occasionally relieved by Taglioni’s choreography and they all agreed that Marie Taglioni and Adam’s score were the ballet’s only saving grace; one critic described Adam’s score as “full of freshness and grace”. Had Marie not danced in it and had Adam not been the composer, the ballet would probably have been a complete disaster. Despite not receiving a successful reception at its world première, La Fille du Danube remained active in the Paris Opéra repertoire for some time. On the 22nd October 1838, Fanny Elssler made her début as Fleur des Champs and on the 26th July 1840, Marie Taglioni performed in the ballet’s second act for her benefit performance. La Fille due Danube was brought to London when it was staged at Drury Lane by the English dancer and Ballet Master George Gilbert. It made its London début on the 21st November 1837, with Gilbert’s wife, the Prima Ballerina Eliza Ballin as Fleur des Champs.

La Fille du Danube in Russia

The following year in 1837, Taglioni and his daughter traveled to Saint Petersburg, where Marie Taglioni made her Russian début in La Sylphide on the 28th September [O.S. 6th September] 1837 at the Imperial Bolshoi Kammeny Theatre. Her Saint Petersburg début was a huge success, with the Russian balletomanes and critics becoming completely enchanted by the famous ballerina. That same year, her father revived and restaged La Fille du Danube for Marie’s benefit performance on the 1st January 1838 [O.S. 20th December 1837], in which she was partnered by Nikolai Goltz, who danced Rudolph. Unlike Taglioni’s other works, the Russians were unfamiliar with La Fille du Danube and the reception in the Imperial capital was very different from what the ballet had experienced had its world première. The Saint Petersburg production enjoyed a very successful reception and the critic from the Severnaya pchela wrote:

“The ballet presented yesterday, La Fille du Danube, had a marvellous success. The balletmaster Mr Taglioni, the creator of the ballet, who produced it on our stage, was called for after the first and second acts. Mlle Taglioni was never so captivating as on this evening. The calls for her were endless; we lost count of them.”1

La Fille du Danube was so well-received in Saint Petersburg that it was performed on each of the dozen nights of ballet that followed in the next month. Marie Taglioni performed in La Fille du Danube for the final time in St Petersburg in 1842, a week before her final performance in Russia. La Fille du Danube was to be one of the two ballets by Filippo Taglioni to survive in Russia following the departures of both the Ballet Master and his daughter from the country, the other being La Sylphide.

Petipa’s revival

In 1880, Tsar Alexander II, who had seen Marie Taglioni in the ballet, requested for La Fille du Danube to be revived. Although reviving this particular ballet went against Petipa’s better judgement, he could not ignore the wishes of the Tsar and set to work on reviving La Fille du Danube for the benefit performance of Ekaterina Vazem. For this revival, Petipa included new musical additions and revisions by Ludwig Minkus and the revival was premièred at the Imperial Bolshoi Kammeny Theatre on 8th March [O.S. 24th February] 1880, with Vazem as the now nameless Daughter of the Danube and Pavel Gerdt as Rudolph. Vazem cared little for the ballet, for she considered it to be “flat”, that the heroine’s part was “not the most effective” and even claimed that “the mounting of the ballet looked quite wretched”. However, she acknowledged that the première was met with much enthusiasm from the public and that Gerdt’s performance was “incomparable”.

At the wish of Alexandre II the old ballet ‘La Fille du Danube’ was revived the next season. The tsar had once seen the celebrated Marie Taglioni in it, and wanted to experience that impression of his youth again. ‘La Fille du Danube’, therefore, was a ballet in some sense historical and, in any event, very archaic. [Filippo] Taglioni was its author, not a very gifted balletmaster who produced works exclusively for his celebrated daughter whose artistic charm concealed the weakness of her father’s compositions. Since Taglioni’s time the choreographic art in general, and matters of theatrical production in particular, have made such progress that in the 1880s ‘La Fille du Danube’ could hardly amount to anything particularly interesting. Its story is inspired by the old Austrian legend about Donauweibchen, and concerns the girl water-spirit who lives an earthly life and captivates a young page.

After the powerfully dramatic ballets of Perrot and Petipa it was rather ‘flat’. However Petipa tried to rejuvenate this old piece with new dances, his efforts proved unsuccessful. The ballet had neither scenic effects, to which the audience was accustomed from our balletmaster’s latest works, nor brilliant dances which impressed the public. Adam’s music seemed very antiquated and yielded significantly to his other compositions, especially ‘Giselle’. Moreover, in the old days ‘La Fille du Danube’ on our stage stood out for its luxurious mise-en-scène, whereas in revival, because of the economy introduced by Baron Kister, there could be no thought of luxury in this respect.

The first performance of ‘La Fille du Danube’ in this revival was given as my benefit performance in February 1880. I took the title part, and remember having success with the classical trio in the first act with [Alexandra] Shaposhnikova and [Pavel] Gerdt, and with the waltz to Lanner’s music in the second act, performed with Gerdt. In general, the heroine’s part was not the most effective. In the ‘earthly’ scenes at the beginning of the ballet I had to portray some kind of caricature, all but simple-minded. To Gerdt’s incomparable performance in the role of the page I have already referred. The mounting of the ballet looked quite wretched, For all the minuses of this production, however, the public, perhaps fascinated by the legend of the furore which Taglioni created in ‘La Fille du Danube’, came to the theatre in throngs.”

- From Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St Petersburg Bolshoy Theatre, 1867-1884, Ekaterina Ottovna Vazem, Chapter 11 (quoted in A Century of Russian Ballet, 1810-1910 by Roland John Wiley, 2007)

Since the turn of the 20th century, at least two productions of La Fille du Danube have been staged. In 1996, Paul Chalmer created a new production for the Balletto dell’Arena di Verona and in 2006, Pierre Lacotte created another new production for the Théâtre Colón in Buenos Aires.

Sources

- Guest, Ivor (2008) The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Alton, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Guest, Ivor (1954) The Romantic Ballet in England. Hampshire, UK: 2014 ed. Dance Books Ltd

- Wiley, Roland John (2007) A Century of Russian Ballet, 1810-1910. Alton, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Meisner, Nadine (2019) Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master. New York City, US: Oxford University Press

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.

- Quoted in Severnaya pchela, 1837, No. 291 [22 Dec.], p. 1162 ↩︎