Grand ballet in four acts and seven scenes with an apotheosis

Music by Ludwig Minkus

Libretto by Marius Petipa and Sergei Khudekov

1877 décor by Mikhail Bocharov (Act 1, scene 1), Matvei Shishkov (Act 1, scene 2 and Act 2), Ivan Andreyev (Act 3, scenes 1 and 3), Heinrich Wagner (Act 3, scene 2) and Andrei Roller (Act 4 and apotheosis)

Costumes by Ivan Panov

1900 décor by Adolf Kvapp (Act 1, scene 1), Konstantin Ivanov (Act 1, scene 2, Act 4 and apotheosis), Petr Lambin (Act 2, Act 3, scenes 1 and 2) and Orest Allegri (Act 3, scene 2)

World Première

4th February [O.S. 23rd January] 1877

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, Saint Petersburg

Original 1877 Cast

Nikiya

Ekaterina Vazem

Solor

Lev Ivanov

Hamsatti

Maria Gorshenkova

The Great Brahmin

Nikolai Goltz

The Rajah

Christian Johansson

Première of Petipa’s final revival

16th December [O.S. 3rd December] 1900

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1900 Cast

Nikiya

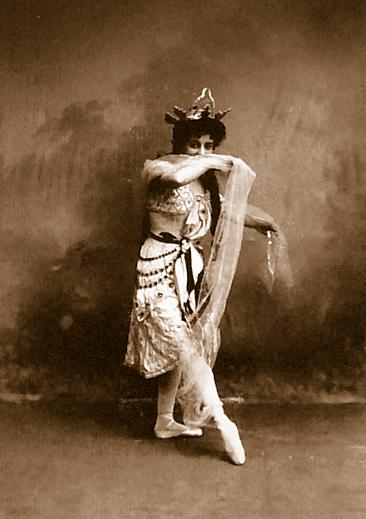

Matilda Kschessinskaya

Solor

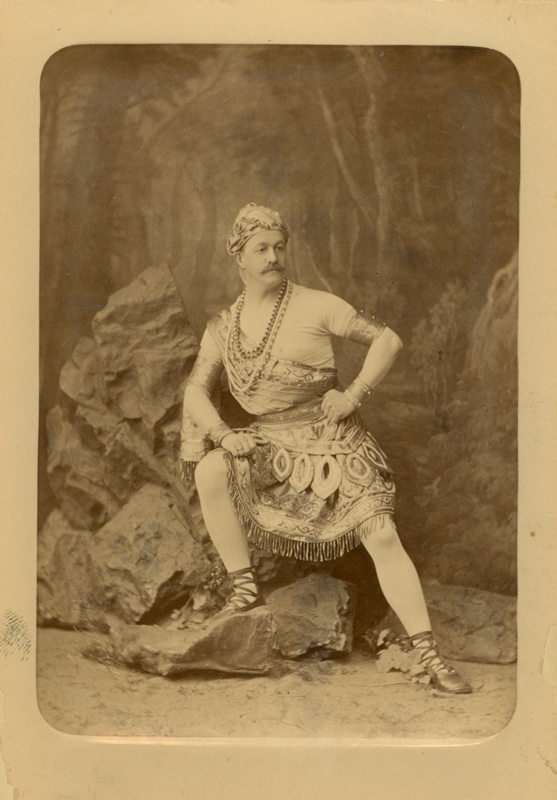

Pavel Gerdt

Gamzatti

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

The Great Brahmin

Felix Kschessinsky

The Rajah

Nikolai Aistov

The Three Shades

Julia Sedova

Varvara Rykhliakova

Anna Pavlova

History

The original production

La Bayadère is the most famous and celebrated of Petipa’s exotic ballets. Set in Ancient India, it touches on the theme of the oriental exotic, which was a very common theme used throughout 19th century ballet, with the creations of such ballets as Filippo Taglioni’s Le Dieu et la Bayadère, which premièred in Paris in 1830. In 1838, the fascination with the exotic increased when a troupe of dancers from India visited Paris. Ballets set in India were nothing new to Petipa; he had danced in Le Dieu et La Bayadère in Bordeaux and his first wife Maria danced in a revival that was staged in Saint Petersburg on the 22nd May [O.S.10th May] 1854. Petipa also claimed to have staged dances for Zina Richard’s performance as the bayadère at the Paris Opéra in 1856 and he would have known his brother Lucien’s ballet Sacountala, which premièred at the Paris Opèra on the 14th July 1858, which was based on the play of the same name by the Indian poet Kalidasa. All these works could have been the inspiration for La Bayadère, though another possible source was likely to have been the Prince of Wales’s visit to India in 1875, which was covered by every European newspaper and magazine. The libretto was written by Sergei Khudekov, though years later, Petipa claimed sole authorship in a letter to the Saint Petersburg Gazette. The likelihood is that the writing of the libretto was probably a joint collaboration between the two men since Petipa would have been more familiar with the aforementioned works than Khudekov.

Despite the ballet’s setting in Ancient India, Ludwig Minkus’s music, even in the character numbers, makes barely any gesture to traditional forms of Indian dance and music. The ballet was essentially a vision of the Southern Orient through 19th century European eyes. Although some sections of Minkus’s score contain melodies that are reminiscent of the Southern Orient, his score is a definitive example of the musique dansante in vogue at that time and does not stray at all from the usual string of lightly orchestrated melodious polkas, adagios, Viennese-style waltzes and the like. In that same regard, Petipa’s choreography contained various elements that reminded the spectator of the ballet’s setting, but never once did the Ballet Master stray from the canon of classical ballet.

La Bayadère was created and staged for the benefit performance of Ekaterina Vazem, who was cast as Nikiya. In her memoirs, Vazem reflects on how the ballet was her favourite:

“In the ballet my next new part was that of the bayadère Nikiya in La Bayadère, produced by Petipa for my benefit performance at the beginning of 1877. Of all the ballets which I had occasion to create, this was my favourite. I liked its beautiful, very theatrical scenario, its interesting, lively dances in the most varied genres, and finally Minkus’s music, which the composer managed especially well as regards melody and its co-ordination with the character of the scenes and dances.”1

Petipa spent almost six months staging La Bayadère. During the rehearsals, he clashed with Vazem, first over Nikiya’s dance with the basket of flowers and then, the matter of her entrance in the ballet’s final Grand Pas d’action of the fourth act, while also experiencing many problems with the set designers who constructed the ballet’s elaborate stage effects. Vazem recollects the argument with Petipa regarding her entrance in the Grand Pas d’action in her memoirs:

“… for my entrance Petipa again staged something absurd consisting of some small pas. I did not hesitate to reject this version, which was “not in the music” and neither did meet the general idea of this dance. Something more impressive was required for the entrée of the shadow that appeared in the middle of the wedding celebration than those indistinguishable trifles invented by Petipa. Petipa was already irritated. The last act did not go well for him at all; he wanted to finish the production of La Bayadère at all costs on that day. He hastily put on for me something else, even less successful, and again I calmly objected that I would not dance this. Then he completely lost his temper and shouted in rage:

“I don’t understand what you need to dance? You can’t do this, and you can’t do anything else! .. What kind of talent you are?”

Without saying a word, I took my things and left the rehearsal, which thus came to end.

The next day, as if nothing had happened, I again started a conversation with Petipa about my entry in the last act. … Hurrying to finish the production, he told me:

“If you can’t dance anything else do what Madame Gorshenkova does.”

Gorshenkova, who danced the princess [Gamzatti], was extremely light, and her entrée consisted of a series of high jumps – jetés from the depths of the stage to the ramp. By offering me to perform her pas, the choreographer wanted to “pinch” me: I was a “terre-a-terre” ballerina, with expertise in technically complex, virtuoso dances, but I had no ability to “fly” at all. But I didn’t give up.

“Very well,” I said, “but just to make it different, I will do the same pas not from the last, but from the first coulisse.”

The latter is much more difficult because the slope of the stage cannot be used for the prolonging effect of the jump.

“As you wish, as you wish,” replied Petipa and began the rehearsal.

At primary rehearsals I never danced [the entry], limiting myself to an approximate outline of my pas and not even putting on dancing shoes. During the pas d’action, I just walked around the stage among the dancers.

Then came the day of the first orchestra rehearsal at the theatre. Here, of course, I had to take part in the dances. The choreographer, as if wishing to distance himself from responsibility for pas d’action, repeated to the artists:

“I don’t know that Madame Vazem will dance, she never danced at rehearsals.”

The rehearsal went on as usual. Finally we got to the last action and to the pas d’action. I stood in the first coulisse, waiting for my entry. Inside I was seething – the true grit of passion spoke in me. I wanted to teach the arrogant Frenchman a lesson and show him what a talent I am. Here comes my way out. At the first sounds of accompanying music, I gathered all my strength – my nerves seemed to be tripled – and literally flew onto the stage, jumping even over the heads of the kneeling dancers in the group. After crossing the stage in three jumps, I stopped dead on the spot. The entire troupe on stage and in the auditorium burst into thunderous applause. Petipa, who was on the stage, apparently at once realized his unfair attitude towards me. He came up to me and said:

“Madame, I am sorry. I am a fool…””

From Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St Petersburg Bolshoy Theatre, 1867-1884, Chapter 11, by Ekaterina Ottovna Vazem (quoted in A Century of Russian Ballet, 1810-1910 by Roland John Wiley, 2007)

Petipa was also worried that his new work would play to an empty house, as the Director Karl Kister increased the ticket prices to be higher than the Italian Opera, which at the time were expensive. Despite some of the difficulties experienced during the period of the creation, when the ballet was completed, what Petipa and Minkus presented was a great dramatic work set in an exotic locale that told a story of love, betrayal, murder and vengeance.

Libretto

The first scene of the first act takes place outside a Hindu temple (see fig. 3). A group of warriors arrive and among them is Solor, the noblest of them all. They are setting out on a tiger hunt. Solor stays behind, claiming he wishes to pray alone by the sacred fire that burns outside the temple, but he really intends to meet his secret lover, the beautiful bayadère Nikiya, who has been chosen as head bayadère for a celebratory ritual that is about to take place. Solor implores Madhavya, the head of the fakirs, to tell Nikiya he will wait for her. Madhavya agrees and Solor hides as the priests and the Great Brahmin emerge from the temple. Madhavya summons the other fakiers to prepare the sacred fire and the bayadères arrive as the ritual begins. The ritual scene contains three dance numbers – the Dance of the Bayadères, a simple dance with the women in heeled shoes performing consistent tombés, the Dance of the Fakirs, which includes the fakirs jétéing over the fire, and finally, the Variation of Nikiya. However, the Great Brahmin, overwhelmed by Nikiya’s beauty, suddenly declares his love for her and promises to lay all of India’s riches at her feet, but Nikiya rejects him, reminding him of his place in the temple. The bayadères bring water from the sacred spring to the fakirs and Madhavya delivers Solor’s message to Nikiya, who is delighted that her beloved is close by. When everyone returns to the temple, Solor returns and watches Nikiya as she sits at a window and plays a romantic melody on her veena (an Indian guitar). The lovers then unite as the fakir guards their meeting. Solor and Nikiya agree to elope and swear eternal love and fidelity to one another over the sacred fire, unaware that the Great Brahmin has caught them. Madhavya alerts them to the arrival of the other bayadères, who have come to fetch water from the sacred spring. Nikiya sneaks back into the temple and the warriors return, having successfully caught a tiger (in the original production, the tiger was captured alive, not killed, and a real tiger was apparently used). As the warriors depart, Nikiya reappears at the window and bids goodnight to Solor, who promises to remember his vow. However, the Great Brahmin, fuelled with anger and jealousy, emerges from the temple and begs the gods to help him destroy his rival.

The second scene takes place in the Rajah’s palace, opening with the warriors playing chess when the Rajah enters, who has decided that the time has come for Solor is to marry his daughter Gamzatti (in the original 1877 production, she was called Hamsatti), who he has been betrothed to since childhood. The Danse d’Jampe is performed by eight bayadères and afterwards, the Rajah summons Gamzatti. He tells her that she is to marry Solor, presenting a portrait of her intended groom and she is delighted. When the engagement is announced, Solor is not happy for he has not forgotten his vows to Nikiya and attempts to refuse the princess’s hand, but the Rajah is adamant and becomes angry; to deny his wishes would be high treason. Solor has no choice but to comply. Just then, the Great Brahmin enters, demanding a private audience with the Rajah. The Rajah agrees, dismisses everyone and the Great Brahmin tells him of Solor and Nikiya’s relationship and their vow of eternal love in an attempt to do away with his rival. However, his plan horribly backfires when the Rajah to decides that Nikiya must be the one to die. Horrified, the Great Brahmin warns him that to murder a member of the temple will only provoke the wrath of the gods and he and his household would pay a terrible price for such a crime, but the Rajah refuses to back down. The two men depart, unaware that Gamzatti has overheard their conversation and is stunned to learn of her fiancé’s love for another. She summons Nikiya and spitefully invites her to dance at her upcoming wedding, which Nikiya agrees to, before revealing the identity of her future husband. A fight ensues between the women as Gamzatti begs Nikiya to give Solor up. When she fails to persuade her, she offers her jewels, but Nikiya still refuses and, in the heat of the moment, threatens Gamzatti with a dagger, but is stopped at the last minute by a handmaid. As the horrified Nikiya flees, the act closes on Gamzatti swearing to destroy her rival.

The second act takes place in the garden of the Rajah’s palace, where a festival of Badrinata is underway. The act begins with a grand procession that introduces the dancers of the divertissements and presents an idol of the Hindu god Vishnu, but the most distinctive feature is Solor entering on an elephant (just like Queen Nisia in Act 2 of Le Roi Candaule), after which he presents the captured tiger to the Rajah (see fig. 5). While the first act is mostly made up of pantomime, the second act is almost entirely devoted to dance with its multiple divertissements – the danse d’esclaves (dance of the slaves), the Pas des éventails (dance of the fans), which includes among its dancers a group of male students, the valse des perroquets (waltz of the parrots), in which the dancers dance with prop parrots, two pas de quatres performed by four bayadères and perhaps the two most famous dances, the Danse manu and the Pas des guerriers – Danse infernale (aka the Indian Dance). The Danse Manu is especially famous for its concept of a woman balancing a jug of milk on the top of her head, with two female students attempting in vain to retrieve some for themselves. In the end, she removes the jug and tips it upside-down, only to reveal that it’s empty. The famous Danse infernale features Madhavya playing a tabla (an Indian drum) with a group of male dancers and a leading couple dancing to the drumbeats. The divertissements come to a close with a coda générale. Afterwards, the story resumes when Nikiya is brought in to dance and she expresses her heartbreak as she dances with her veena, playing a variant of the melody she played the previous night, which further plucks the strings of Solor’s remorse as he watches her. Her mood brightens, however, when she is presented with a basket of flowers, which she is told is a gift from Solor, unaware that it is really from the Rajah and Gamzatti, who have concealed a poisonous snake among the flowers. The snake bites Nikiya when she holds the basket to her chest. The Great Brahmin makes her one last offer – an antidote to the poison if she will renounce her love for Solor in favour of him, but Nikiya refuses and dies in Solor’s arms, remaining true to her vow and pleading with Solor to remember his, while her murder calls down the wrath of the gods on those responsible.

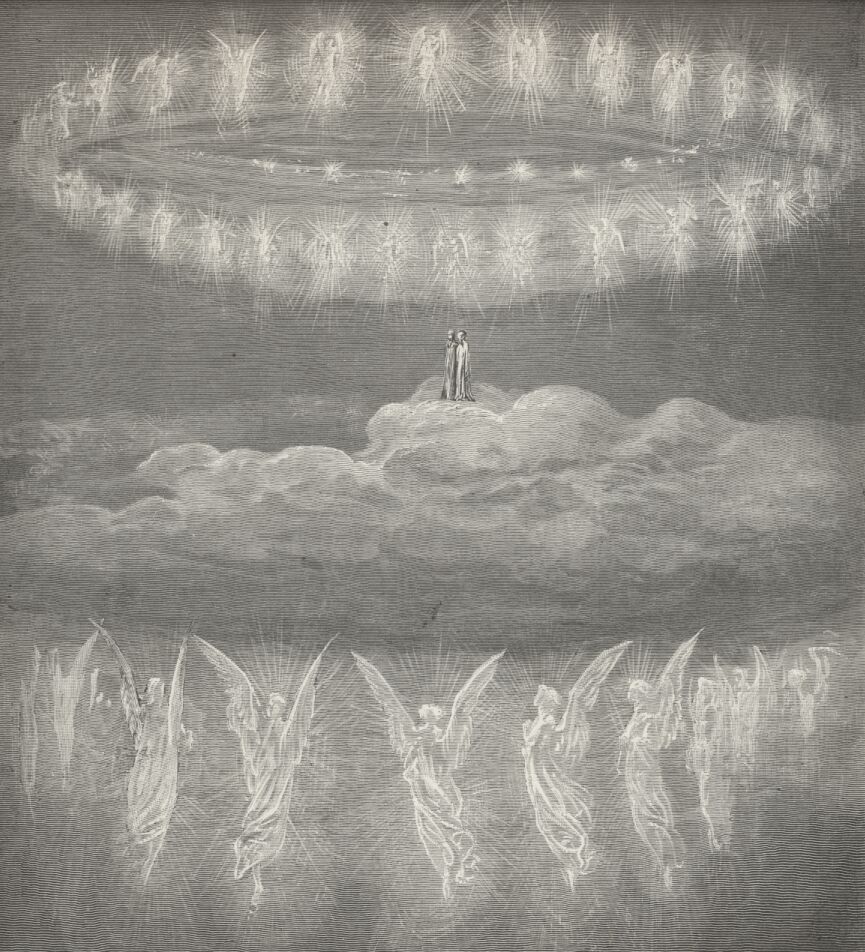

The third act contains the ballet’s most famous and celebrated scene – The Kingdom of the Shades. The curtain rises revealing Solor in his room tormented by grief and guilt by Nikiya’s death and his failure to remain true to his vow. Madhavya enters with a snake charmer and, in an attempt to lift Solor’s spirits, they perform a comic number in which Madhavya dances to the snake charmer’s pungi, but Solor angrily dismisses them. He then receives an unwanted visit from Gamzatti, who tries in vain to win him over. Suddenly, the shade of the weeping Nikiya appears to a new variant of the melody she played on her veena in the first act, but only Solor can see her. Gamzatti worries he is going mad, but Solor sends her away and Nikiya’s shade continues to haunt him. Exhausted, Solor smokes opium and falls asleep, dreaming of Nikiya in a glorious heavenly realm called the Kingdom of the Shades. Petipa staged The Kingdom of the Shades scene as a Grand Pas Classique, but the narrative did not cease. In the original 1877 production, the scene was set in an illuminated castle in the sky and contained a huge corps de ballet of sixty-four dancers. Petipa’s simple and academic choreography was to become one of his most celebrated compositions, with the famous Entrance of the Shades arguably his most celebrated composition of all.

The Entrance of the Shades was inspired by Gustav Doré’s illustrations for Dante’s Paradiso from The Divine Comedy (see fig. 6), with each dancer of the sixty-four strong corps de ballet clad in white tutus with veils stretched about their arms. Each of the dancers makes her entrance one by one down a long winding ramp from upstage right with a simple arabesque (fondu) and into cambré, followed by an arching of the torso with arms in fifth position, followed by two steps forward. With the last two steps, she makes room for her sister shade and the combination continues thus in a serpentine pattern until the entire corps de ballet has filled the stage in eight rows of eight. Then follows simple movements en adage to the end. Petipa left the Entrance of the Shades free of technical complexity – the unison of the whole and the effect of the descending ballerinas is the challenge as a mistake from one dancer would spoil the entire scenario.

When Solor enters, Nikiya appears, accompanied again by her melody, and Solor begs for forgiveness. In a scène dansante to a solo violin accompaniment (one of several composed especially for the violinist Leopold Auer), Nikiya forgives him and the lovers reconcile in a grand adagio where they are accompanied by the corps de ballet. After the variations of the three solo shades comes a very interesting passage – the Variation of Nikiya with the Veil, which sees Nikiya entering holding one end of a long tulle veil, while the other end is attached to a wire in the rafters above the stage. When Nikiya releases the veil, it flies away up into the rafters, as if it were “supernaturally guided” (see video 1). Ekaterina Vazem briefly mentions this effect in her memoirs:

“I had a great success, in the variation, accompanied by [Leopold] Auer’s violin solo, with the veil which flies upwards at the end” – From Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St Petersburg Bolshoy Theatre, 1867-1884, Chapter 11, by Ekaterina Ottovna Vazem (quoted in A Century of Russian Ballet, 1810-1910 by Roland John Wiley, 2007)

The scene concludes with a coda, during which there is a moment where Solor attempts in vain to grasp Nikiya, presenting the image of the hero pursuing the elusive woman he loves. Nikiya performs a sequence of saut de basques and jétés in a circle and when the music is repeated for Solor, he performs the same sequence. According to Fyodor Lopukhov, the purpose for this is that it is creating a dialogue between the two dancers; in other words, it further deepens the connection between Solor and Nikiya as he pursues her in his longing to be reunited with her. At the end of the coda, Solor catches Nikiya when the stage goes dark and the dream comes to an end. The act closes with a scene in which Solor is awakened from his dream by Madhavya and the warriors, who remind him that the day of the wedding has arrived and he reluctantly follows them.

The fourth and final act gives the ballet a perfect climatic ending to all the drama. Taking place in the Rajah’s palace, the wedding is underway. The Rajah, Gamzati and Solor arrive, but Solor is deeply distant as he can only think of Nikiya. The wedding begins with a dance number called the Dance of the Lotus Blossoms, which is danced by twenty-four female students with prop garlands. At one point, the students make a circle in the middle of the stage and tap the floor with their garlands, after which, Nikiya rises up onto the stage via a trap door and dances the remainder of the dance alone. Solor, to whom she is only visible, pursues her, which leaves everyone else thinking that he is losing his reason. This is followed by the Grand Pas d’action performed by Gamzatti, Solor, four bayadères, a cavalier and the shade of Nikiya, as she continues to haunt Solor, reminding him of his vow. Petipa choreographed this number to be performed by two premier danseurs – Lev Ivanov, who was the original Solor, and Pavel Gerdt, who served as an additional cavalier to the aging Ivanov. Both men shared the partnering of Gamzatti and Nikiya and Gerdt performed the dancing and Solor’s variation and there were also moments when they would appear on stage at the same time (see video 2). As the wedding continues, the horrors only escalate as Gamzatti gets an unpleasant reminder of her crime when she is presented with a basket of flowers identical to the one given to Nikiya and the shade of her rival appears to all present. The terrified Gamzatti urges her father to complete the wedding, but before the Great Brahmin can complete the ceremony, in a dramatic climax, the palace is destroyed by a great earthquake sent by the angry gods to avenge Nikiay’s murder, killing everyone within and burying them under the rubble (see fig. 8). The ballet ends with an apotheosis that shows an image of the god Vishnu and the shades of Solor and Nikiya are seen flying away together above the rain to the Heavens, reunited in eternal love.

World première

La Bayadère premièred on the 4th February [O.S. 23rd January] 1877 at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre and it was a renowned success, with The Kingdom of the Shades receiving the most praise. The fourth act was also highly applauded, especially the works of the machinists for the destruction of the palace. In 1900, Petipa staged his final revival of La Bayadère for the dual benefit performances of Pavel Gerdt and Matilda Kschessinskaya, which premièred on the 16th December [O.S. 3rd December], with Kschessinskaya as Nikiya, Gerdt as Solor and Olga Preobrazhenskaya as Gamzatti.

For the 1900 revival, Petipa made some changes, including changing the name of the Rajah’s daughter from Hamsatti to Gamzatti, but the most significant changes were made to The Kingdom of the Shades: the setting was changed from an enchanted castle in the sky on a full-lighted stage to the dark, rocky mountain tops of the Himalayans (see fig. 7) and the number of dancers in the corps de ballet was decreased from sixty-four to forty-eight. For the Grand Pas d’action in the fourth act, new variations were added. Georgy Kyaksht, who acted as the additional cavalier, interpolated a variation that was composed by Minkus for Petipa’s 1874 revival of The Butterfly as Solor’s variation and this is the variation of which the violin repetiteur score is included in the Sergeyev Collection. A new variation may have been added for Gamzatti, but in this case, there is some confusion. The variation that is included in the repetiteur score is what is today known as the famous Variation of Dulcinea in the Dream scene of Don Quixote, which was composed by Riccardo Drigo in 1888 for Elena Cornalba’s performance in The Vestal. It was later interpolated into La Bayadère as the Variation of Gamzatti, possibly by Julia Sedova, who was dancing the role by 1902 and whose name is on the repetiteur score. However, it is unknown if this is the same variation that was danced by Olga Preobrazhenskaya in 1900. According to Col. Vladimir Teliakovsky, a new variation was also added for Nikiya, which was interpolated by Kschessinskaya from Petipa and Minkus’s ballet Mlada.

In 1903, the earliest known performance of The Kingdom of the Shades as an independent piece took place at a gala performance held at Peterhof Palace in honour of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was on a state visit to Russia.

La Bayadère in the 20th Century

La Bayadère was staged by Alexander Gorsky for the Imperial Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow on the 24th January 1904. Gorksy’s production subsequently underwent three revivals (1907, 1910 and 1917) and in the 1917 revival, he presented a more radical version of the ballet, which included finishing with a “wedding feast” as the highlight with all kinds of quasi-authentic Indian arm and finger positions. He also made some quite drastic changes to the Kingdom of the Shades scene, including the use of much more quasi-authentic Indian-style costumes for the shades. The scene was later restored to its original scenario, or at least a version closer to it, by the Bolshoi Premier Danseur Vasily Tikhomirov in 1923.

Of all Petipa’s surviving ballets, La Bayadère is one of the most altered and the alterations that became the standard and traditional choreography known today began after the 1917 Revolution. The most infamous alteration that has since become tradition is the omission of the fourth act. The first production to omit the fourth act was Gorsky’s 1907 revival and his reason for omitting the act was because by then, the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatre’s administration had stopped renting the sets. However, none of Gorsky’s revivals were staged outside of Moscow, so it was not his production that gave way to the tradition. Under the new Soviet regime, La Bayadère reappeared at the former Imperial Mariinsky Theatre on the 23rd November 1919 when it was revived for the benefit of Nikolai Solyannikov for 25 years of service to the Theatres and excluded the fourth act. In 1920, a new production was staged with Olga Spessivtseva as Nikiya, Anatoly Vilzak as Solor and Maria Romanova (the mother of Galina Ulanova) as Gamzatti and Minkus’s score adapted and re-orchestrated by Boris Asafiev. This production holds a significant place in ballet history; according to Lopuhkov, this was the second Petrograd production to omit the fourth act and it was the production that gave way to this most infamous tradition.

Lopukhov claimed that the fourth act was removed because the theatre now lacked the technical staff needed to stage the destruction of the palace, but even this claim does not explain why it was permanently removed from the ballet as it later reappeared on the Russian stage. The fourth act of La Bayadère was performed for the final time in Russia circa. 1924, after which, it disappeared with no concrete explanation, but there are several theories:

- Petrograd was flooded in 1924 and many pieces of décor created for the former Mariinsky Theatre’s stage were destroyed. Among these may have been the décor for Act 4 of La Bayadère and perhaps the post-revolution Saint Petersburg ballet were unable to obtain the funds for new décor.

- A lack of funding supports the second theory, which is that the Mariinsky Theatre lacked the technical staff needed to produce the effects of the palace’s destruction, as Lopukhov claimed.

- A third and more curious theory tells of how the new Soviet regime would not have allowed the performance of a theatrical presentation that included Hindu gods destroying a palace.

It may very well be that all of this factored into the loss of Act 4, but the true explanation for the act’s disappearance still remains unclear. Lopukhov further claims that due to the omission of the fourth act, the 1920 revival was the first production to present the Grand Pas d’action in the second act, giving way to another modern tradition. In one of his many writings, Lopukhov wrote that when the 1920 production was staged, the music for the Grand Pas d’action was cut and rearranged, Nikiya was removed from the number and it was given to Solor, Gamzatti, four bayadères and two cavaliers, completely changing the scenario from Petipa’s pas d’action of Solor being haunted by Nikiya’s shade to a standard pas de huit. In 1932, Agrippina Vaganova staged a new production for the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet, in which she heavily revised the dances for Nikiya. These features included triple pirouettes sur la pointe and fast soutenu turns en dehors, all of which would find a permanent place in the ballet as the traditional choreography for Nikiya.

Eight years later, plans were made to revive La Bayadère again for the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet by Ballet Master Vladimir Ponomarev and the company’s star Premier Danseur Vakhtang Chabukiani. One of the most famous productions known today, it is from this staging that all modern productions of La Bayadère derive. The production retains the original 1900 décor for the first and second acts and it retained Vaganova’s revised choreographic passages for Nikiya, with some new revisions by Natalia Dudinskaya. One of the most notable changes was the transformation of the Variation of Nikiya with the Veil into what is now known as the so-called “Scarf Duet” in The Kingdom of the Shades. Rather than Nikiya performing the variation alone with the veil flying away into the rafters, Solor was added, holding the other end of the veil and exiting halfway through, leaving Nikiya to dance the remainder of the variation alone. It was Dudinskaya who introduced the multiple tours en arabesque associated with this variation today and she also added to the famous fast piqué turns in the Grand coda. The choreography for Solor was completely revised by Chabukiani and it is from his choreographic revisions that the traditional choreography for Solor derives.

Ponomarev and Chabukiani introduced many other new changes that all became standard. The first act, which was originally mostly made up of panntomime, was almost completely changed with the majority of the pantomime being replaced with new dances, something that became a Soviet tradition. For example, Ponomarev rechoreographed the dance of the bayadères in the first scene, transforming Petipa’s simple character dance into a more challenging classical dance number with the dancers wearing pointe shoes. The number for solo flute where Nikiya plays her veena at a window while Solor looks on before their meeting was changed into another variation in which Nikiya looks for Solor outside the temple while carrying her water jug on her shoulder. Solor and Nikiya’s love scene, which was originally a purely mimed scene, was completely transformed into the famous pas de deux known today, which was introduced and choreographed by Chabukiani. The closing scene was shortened with the omission of the return of the bayadères and the warriors and Solor and Nikiya’s tender farewell.

Other changes included the retaining of the Grand Pas d’action in the second act. Lopukhov wrote that it was in this revival that the Grand Pas d’action was heavily revised into the traditional version danced today, with only a small fragment of Petipa’s choreography still in use. Ponomarev and Chabukiani’s staging featured new choreographic revisions for Solor by the latter and the replacing of the pas d’action’s original coda with the Coda Générale of the divertissements, in which they introduced the fouetté sequence for Gamzatti that has since become standard. Among Chabukiani’s revisions for Solor was the introduction of the famous variation that is danced in all modern productions, replacing the variation that was introduce dby Nikolai Legat in 1900. The famous traditional variation for Gamzatti is a variation composed by Riccardo Drigo for Queen Nisia in the Pas d’Aphrodite from Le Roi Candaule and the choreography is by Pyotr Gusev. However, it is unclear how this variation ended up in La Bayadère, but there are two possibilities – it could have been interpolated into the ballet by Olga Preobrazhenskaya for the 1900 revival and was then replaced by the variation performed by Julia Sedova, or it is a Soviet addition. By 1940, the fourth act was long gone and it had become tradition to end La Bayadère with The Kingdom of the Shades in which the curtain falls on Solor and Nikiya surrounded by the corps de ballet of shades. The production by Ponomarev and Chabukiani premièred on the 10th February 1941 at the Kirov Theatre, with Natalia Dudinskaya as Nikiya and Chabukiani as Solor and the Mariinsky company continues to perform the production to this day.

In the years following the 1941 production, more new dance numbers were introduced to La Bayadère in Russia and have remained in the ballet ever since. One of the most famous additional numbers is the Dance of the Golden Idol. This number was created by the Russian danseur Nikolai Zubkovsky in 1948 for the 1941 production. The music is by Minkus, but it is not from his score for La Bayadère: it is a Persian march that he composed for Petipa’s revival of The Butterfly. Interestingly, the music is not even a march, but a waltz in 5/4 time, for in the nineteenth century, composers used the 5/4 time signature when they needed to portray ‘the exotic’. In 1954, Konstantin Sergeyev choreographed and added a new pas de deux for Dudinskaya in the second scene that is performed by Nikiya, a male slave and two female students. This pas de deux is known as the so-called Pas de deux for Nikiya and the Slave. The music for this number is not by Minkus, but by Cesare Pugni: it is the adage for his Pas des fleurs from the second act of Esmeralda.

La Bayadère in the West

While La Bayadère was a prominent member of the Russian repertoire during the 20th century due to the success of Ponomarev and Chabukiani’s production, it was not performed for many years in the west. In 1923, Nikolai Sergeyev staged a new edition of The Kingdom of the Shades for the Riga Opera Ballet during his tenure as Ballet Master in the Latvian capital. In this edition, the excerpt was staged in two scenes under the title The Rajah’s Dream. In 1927, he was invited by Anna Pavlova to stage La Bayadère for her company, but unfortunately, the staging was never achieved because Pavlova’s dancers could not embrace the ballet and/or take it seriously. One of Pavlova’s dancers, Harcourt Algeranoff gives a very sarcastic account of the failed attempt in his book My Years with Pavlova:

“A few days after the long English tour started Nicolai Sergueeff arrived to stage La Bayadère for the Company. Pavlova began rehearsing the pas de deux, and I can see her now as she held the à la seconde on point, while Novikoff left her and then returned to her and took her hand. The corps de ballet had very dull work, and Sergueeff, who could not speak any English at all at that time, kept trying to make the character dancers do the classic work.

The English girls tried to say ”Ya Charakternaya” (I am a character dancer) but to no effect. Then he started rehearsing the Fakir’s dance, with John Sergeieff and Aubrey Hitchins. It was so démodé that the Company were having hysterics – only Sergueeff was serious.

Pavlova saw it, and then she realised that it was no good trying to revive this old monstrosity which had once been good in Russia; the Fakir’s dance settled it. Sergueeff was paid and returned to Paris. No diplomacy could soothe his hurt. The Rajah’s Dream, as he often called it in later years, was a great favourite of his (twenty years later he gave the choreography to Mona Inglesby as a wedding present!). He never spoke kindly of Pavlova afterwards.” – Harcourt Algeranoff: My Years with Pavlova, p.165

Sergeyev later staged The Rajah’s Dream for Olga Spessivtseva in Paris in 1926 when the Sultan of Morocco visited France and inaugurated the first Paris Mosque. The performance took place on the 26th July 1926 with Spessivtseva as Nikiya and Serge Peretti as Solor. In 1947, during his tenure as Ballet Master of International Ballet, Sergeyev suggested to Mona Inglesby that he should stage The Kingdom of the Shades for the company, but the staging never came to fruition because Inglesby faced the same problems as Pavlova had, as she recollected:

“Maestro had persuaded the management that it would be a good investment to mount one act of La Bayadère – the well known Kingdom of the Shades sequence. He asked me to dance the principal role, but I felt unable to take on any more work at that time, and I also thought it would be a compliment to Nana Gollner, as our guest artist, to offer her the role, and eventually this was agreed upon.

Ever conscious of the delicate financial balance of the company, Maestro offered us costumes he had retained from his former group, which he had formed a short time after leaving Russia, and we agreed to look them over. In the meantime rehearsals progressed, and the company was fully rehearsed with Nana and Paul [Petroff]. I gathered that they very much disliked the old fashioned music, but there was nothing we could do about that.

When the dress rehearsal was called on stage, Maestro’s costumes proved to be rather tired looking, and below the standard to which the company was accustomed. Time was pressing, but it was an embarrassing situation, and after an emergency meeting it was decided to call in Hein Heckroth to design some new costumes at short notice.

But before any further steps could be taken, Nana suddenly expressed her extreme dissatisfaction at the choreography as a whole. It was a little late for such a pronouncement, yet unfortunately her opinion spread throughout the cast. Maestro, having already spent considerable time and effort on the production, was exceedingly upset. He begged me to take on the role as he had originally intended, so the production might go on, but I was fully stretched and quite unable to take on a heavier workload. He would not consider anyone else, so the ballet had to be postponed indefinitely.

It was an extraordinary situation that two hitherto co-operative principal artists had suddenly opposed him in this way, and at such a late stage, but sadly I was quite unable to help him. The company ultimately decided to put all available finances into the full length Sleeping Princess instead, so La Bayadère never came to fruition, and the whole incident closed a sadly downbeat note. It did not, however, detract from the warmth in all Nana and Paul’s other work, and we continued with a pleasant collaboration throughout the rest of their time with the company.

Unfortunately Maestro was not forgiving. “They do not understand”, he said, and his eyes went very cold. Personally, I found the choreography of La Bayadère quite enchanting in spite of the old fashioned music, and I was very sad that the ballet never came to be performed by International Ballet.” – Mona Inglesby: Ballet in the Blitz, p.96-98

Taking into account the experiences of Sergeyev, Pavlova and Inglesby, it is fair to argue that had it not been for the tastes of English and American dancers in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, La Bayadère would probably have become a permanent and celebrated member of the western repertoire much earlier than it did, but that was not to happen until the 1960s.

In 1961, the ballet reappeared in the west when The Kingdom of the Shades was staged for the Teatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro by Eugenia Feodorova on the 12th April and that same year, on the 4th July, it was performed by the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet at the Palais Garnier in Paris and it was this staging that won the ballet’s most famous scene widespread interest and recognition. In 1963, Sir Frederick Ashton commissioned Rudolf Nureyev to stage The Kingdom of the Shades for the Royal Ballet, as Nureyev was very familiar with the scene having danced in the full-length ballet in Russia. Sir John Lanchberry re-orchestrated and arranged Minkus’s score and Nureyev danced the role of Solor with Dame Margot Fonteyn in the role of Nikiya. The Royal Opera House première of The Kingdom of the Shades was a huge success and is considered to be one of the most important events in the history of ballet. However, it would not be for another nineteen years that the first full-length western production of La Bayadère would be staged when, in 1980, Natalia Makarova staged that very production for American Ballet Theatre.

Makarova based her production on the Ponomarev/Chabukiani version, which she had danced in during her career with the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet. Makarova’s production deviates further from Petipa’s version, however; the music was completely rearranged and re-orchestrated by Lanchberry, nearly all of the numbers of the Grand divertissements of the second act were cut and Makarova introduced a brand new version of the missing final act that she completely created and choreographed herself to a pastiche of Minkus’s music that Lanchberry arranged and put together from various numbers in the ballet, most notably the first scene from the third act. Makarova’s La Bayadère premièred on the 21st May 1980 at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York and was broadcast live on PBS. Makarova, herself, danced Nikiya, but sustained an injury during the first act and had to be replaced by Marianna Tcherkassky. Dancing the role of Solor was Sir Anthony Dowell and Cynthia Harvey danced Gamzatti. Makarova’s production was a huge success and has remained a prominent member of the ABT repertoire ever since. In 1990, Makarova staged her production for the Royal Ballet and since then, has staged it for various companies around the world.

In 1991, Rudolf Nureyev began plans to stage a new production of La Bayadère for the Paris Opera Ballet. This would be the final ballet that Nureyev would stage since he was dying from AIDS and knowing this, the French cultural administration granted him an enormous budget for the production and he received more funding from private donors. Like Makarova’s production, Nureyev’s staging is derived from the Ponomarev/Chabukiani version and he turned to his old friend and dance partner, the former Kirov Prima Ballerina Ninel Kurgapkina for assistance in staging the work. Nureyev staged the traditional choreography with his own choreographic touches. It was also his intention to stage the fourth act, but his failing health further deteriorated and he ran short of money, so, in the end, he chose to remain faithful to the Soviet tradition of ending the ballet with the Kingdom of the Shades scene. He commissioned the opera designer Enzio Frigerio and his wife opera designer Franca Squarciapino to design the décor and costumes. Frigerio took inspiration from the Taj Mahal, the architecture of the Ottoman Empire and the designs for the 1877 production for the décor, while Squarciapino took inspiration from ancient Persian and Indian paintings for the costume designs. Nureyev’s production of La Bayadère premièred on the 8th October 1992, with Isabelle Guérin as Nikiya, Laurent Hilaire as Solor and Élisabeth Platel as Gamzatti. The production was a huge success and Nureyev was awarded with the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Minister of Culture. The première was also a special occasion for many as Nureyev died three months later.

Since Makarova’s production, there have been various productions that introduced a new version of the missing final act, but it was not until 2002 that the fourth act returned to the stage when Sergei Vikharev staged a new production for the Mariinsky Ballet. This was the second of Vikharev’s historical productions that were based on the historical documents and the notation scores of the Sergeyev Collection (the first being The Sleeping Beauty, staged in 1999). Although this production was labelled as a “reconstruction”, Vikharev retained most of the Soviet choreography and used only a small amount of the notated choreographic passages. Vikharev’s production marked the return of the long-lost fourth act to Russia, restoring the Dance of the Lotus Blossoms and the Grand Pas d’action to its proper place and original scenario, but his stagings of these numbers were not devoid of alterations from the notation scores. For example, Nikiya’s part in the Dance of the Lotus Blossoms was omitted and the entrée and coda of the Grand Pas d’action were expanded to add more dancing, which included a fouetté sequence for Gamzatti in the coda.

Vikharev’s production of La Bayadère premièred on the 31st May 2002, with Daria Pavlenko as Nikiya, Igor Kolb as Solor and Elvira Tarasova as Gamzatti, but was met with hostility in Saint Petersburg, especially from the Mariinsky dancers and coaches, who were too reluctant to part ways with the version they were familiar with, though it received a warmer reception in the west. The production has since been retired from the Mariinsky repertoire and the company continues to perform in the 1941 Ponomarev/Chabukiani staging.

In 2018, for Petipa’s bicentenary, the world saw a second historical production of La Bayadère that was staged by Alexei Ratmansky for the Staatsballett Berlin. Like Vikharev, Ratmansky consulted the Sergeyev Collection notation scores, but unlike the former, he successfully reconstructed and staged the notated choreographic and mime passages. Ratmansky also found help in notation scores that were made by Alexander Gorsky, which were released from the Moscow archives earlier that year. Many unknown and forgotten details were restored in this production: for example, the love scene between Solor and Nikiya in the first act was restored to a purely mime scene; the Danse des esclaves from the divertissements of the second act returned to the stage after being absent for decades; the Variation of Nikiya with the Veil was restored to its original concept, including the flying away of the veil and Nikiya’s role in the Dance of the Lotus Blossoms in the fourth act was restored, only a trap door was not used for Nikiya’s entrance since the Berlin Opera House stage does not have one.

La Bayadère – Trailer – Staatsballett Berlin

Related pages

Footnotes

- From Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St Petersburg Bolshoy Theatre, 1867-1884, Chapter 11, by Ekaterina Ottovna Vazem (quoted in A Century of Russian Ballet, 1810-1910 by Roland John Wiley, 2007) ↩︎

Sources

- Nadine Meisner (2019) Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master. New York City, US: Oxford University Press

- Jane Pritchard with Caroline Hamilton (2012) Anna Pavlova: Twentieth-Century Ballerina. London, UK: Booth-Clibborn Editions

- Harcourt Algeranoff (1957) My Years with Pavlova. Kingswood, Surrey: William Heinemann Ltd

- Mona Inglesby with Kay Hunter (2008) Ballet in the Blitz. Debenham, Suffolk, UK: Groundnut Publishing

- Tim Scholl (1994) From Petipa to Balanchine: Classical Revival and the Modernization of Ballet. Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge

- Roland John Wiley (2007) A Century of Russian Ballet. Alton, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Michael Stegemann. CD Liner notes. Trans. Lionel Salter. Léon Minkus. Paquita & La Bayadère. Boris Spassov Cond. Sofia National Opera Orchestra. Capriccio 10 544.

- Staatsballett Berlin: Souvenir program for La Bayadère. Staatsoper Berlin, 2018

- Royal Ballet: Souvenir program for La Bayadère. Royal Opera House, 1990

- Mariinsky Ballet: Souvenir program for La Bayadère. Mariinsky Theatre, 2001

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.