Romantic ballet in two acts

Music by Adolphe Adam

Libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Théophile Gautier

World Première

28th June 1841

Salle Le Peletier, Paris

Choreography by Jules Perrot and Jean Coralli

Original 1841 Cast

Giselle

Carlotta Grisi

Duke Albert of Silesia

Lucien Petipa

Hilarion

Jean Coralli

Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis

Adèle Dumilâtre

Saint Petersburg Première

30th December [O.S. 18th December] 1842

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Original 1842 Cast

Giselle

Elena Andreyanova

Première of Petipa’s first revival

17th February [O.S. 5th February] 1884

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1884 Cast

Giselle

Maria Gorshenkova

Duke Albrecht of Silesia

Pavel Gerdt

Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis

Sofia Petrova

Première of Petipa’s second revival

1887

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1887 Cast

Giselle

Emma Bessone

Duke Albrecht of Silesia

Enrico Cecchetti

Première of Petipa’s third revival

17th September [O.S. 5th September] 1899

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1899 Cast

Giselle

Henriëtta Grimaldi

Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

Première of Petipa’s final revival

13th May [O.S. 30th April] 1903

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1903 Cast

Giselle

Anna Pavlova

Duke Albrecht of Silesia

Nikolai Legat

Hilarion

Pavel Gerdt

Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis

Julia Sedova

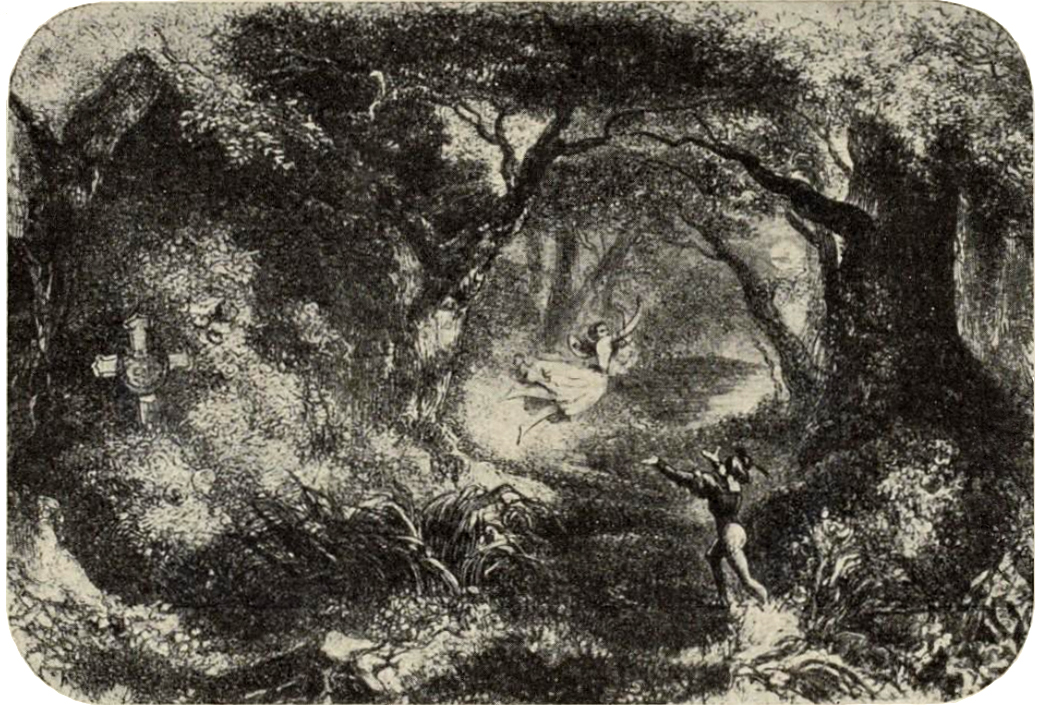

Plot

Set in medieval Germany, Giselle, a beautiful young peasant girl, a free spirit, is in love with the handsome stranger, “Loys”, who in truth is the Duke Albrecht and is betrothed to the Princess Bathilde. When the forester, Hilarion, also in love with Giselle, exposes his rival’s true identity, the consequences are tragic – Giselle goes mad and dies of a broken heart in Albrecht’s arms. After her burial in the forest, Giselle’s spirit is summoned from her grave to join the Wilis, the vengeful ghosts of young girls who have died before their wedding days. To avenge themselves, they rise from their graves every night and force any man who crosses their path into an endless dance, until he collapses and dies of exhaustion. When a remorseful Albrecht visits Giselle’s grave, she appears to him in spirit form. He begs for forgiveness and Giselle, her love undiminished, forgives him. However, Albrecht is targeted by the Wilis and their merciless queen Myrtha forces him to dance. Unwilling to let him die, Giselle protects her lover, defending him until the morning bells herald the dawn. The Wilis are forced to disappear and Giselle, whose love has transcended death, is forever freed from their power and returns to her grave to rest in peace.

History

Giselle is the most famous of Romantic ballets and is the creation of three great French artists: Ballet Masters Jules Perrot and Jean Coralli and composer Adolphe Adam.

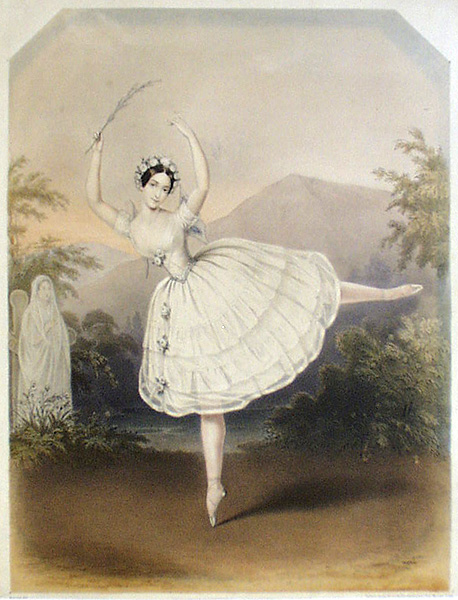

The creation of Giselle could not have come at a better time. Despite the success of Le Diable amoureux in 1840, the ballet of the Paris Opéra had been in a state of decline when compared to its brilliance from years before. Its greatest stars of those years had left the scene – Marie Taglioni was in Saint Petersburg, Fanny Elssler was touring the United States and Lucile Grahn was injured, so, as one observer described, the Paris Opéra was “in a state of widowhood” because the post of première danseuse was now vacant after Pauline Leroux had been indisposed. Some felt that the new Director, Leon Pillet had become so besotted with the singer, Rosina Stoltz that he was neglecting his duties to the ballet, but this was not a fair assumption because, in the last weeks of 1840, he was shown a new light would shine on the Opéra stage and restore most of what it had lost. And that new light was a young dancer named Carlotta Grisi.

Carlotta Grisi was the muse and lover of Jules Perrot: they met in 1836 when Grisi was sixteen and he introduced her to the audiences of London and Paris that same year, which was followed by appearances in Vienna. On the 12th February 1841, Grisi finally made her début at the Opéra in the ballet of Donizetti’s opera La Favorite, in which she was partnered by Lucien Petipa in a pas arranged for her by Perrot. Her performance was a success, the Paris Opéra had a new rising star and discussions for her future with the company began. It was decided that she should dance a more substantial role and a revival of La Sylphide was suggested, for which Perrot was given the task of adding a new pas de trois to the first act that would be performed by James, the Sylph and Effie. However, the idea was abandoned when the ballerina Adèle Dumilâtre protested, claiming that La Sylphide had been promised to her. Subsequently, the Opéra gave into her demands and the new pas de trois was given to Joseph Mazilier to arrange. To contemplate Grisi’s loss of La Sylphide, Perrot arranged two more pas for her, one inserted into La Juive and the other inserted into Don Juan, but the real result of her successful début was still to come.

Pillet, in his quest to find a way to showcase the young dancer, at last thought of a potential new ballet for her. The librettist and dramatist Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges wrote a new libretto entitled La Rosière de Gand, which the directorate accepted in January and offered it to Grisi, but when she read it, she found it to be too long and asked to be given “a more danceable subject” for her first creation at the Opéra. It is possible that she already knew what the “more danceable subject” she requested would be because it may have already been suggested to her by a new admirer, Théophile Gautier, who had conceived an idea that become the ballet Giselle.

Origins of inspiration

The Vila, the Slavic fairy

Gautier first saw Grisi dance at the Renaissance, but he had not been impressed with her. However, his opinion changed when he saw her Opéra début and he wrote:

“Now she sings no longer but dances marvellously. Her strength, lightness, suppleness and originality of style place her at a single bound between Elssler and Taglioni. Perrot’s teaching is there for all to see. Her success is complete and lasting. She has beauty, youth and talent – an admirable trinity.”[1]

Shortly after he wrote these words, he read Heinrich Heine’s L’Allemagne in which he discovered a prose passage about supernatural maidens from Slavic mythology called Wilis:

“In parts of Austria, there exists a tradition… of Slavic origin: the tradition of the night-dancer, who is known, in Slavic countries, under the name Wili. Wilis are young brides-to-be who die before their wedding day. The poor young creatures cannot rest peacefully in their graves. In their stilled hearts and lifeless feet, there remains a love for dancing which they were unable to satisfy during their lifetimes. At midnight, they rise out of their graves, gather together in troops on the roadside and woe to the young man who comes across them! He is forced to dance with them; they unleash their wild passion, and he dances with them until he falls dead. Dressed in their wedding gowns, with wreaths of flowers on their heads and glittering rings on their fingers, the Wilis dance in the moonlight likes elves. Their faces, though white as snow, have the beauty of youth. They laugh with a joy so hideous, they call you so seductively, they have an air of such sweet promise, that these dead bacchantes are irresistible.”[2]

However, rather than a direct account of mythic fairy maidens, Heine’s passage about the Wili is a new interpretation of myths and legends. His Wilis are based on the Vila, a fairy maiden or nymph from Slavic mythology, of which there are various interpretations. The name “Vila” was widely used in southern and central Europe, including western Ukraine, and is attested to the Old Bulgarian language, the oldest written form of Slavic. The Vila (plural, Vili) was mostly known among the South Slavs, but there are some variants present in the mythology of the West Slavs. In all variants, they were beautiful maidens who lived in the forests and mountains and loved to sing and dance. They were said to have lived around water, where they loved to swim, dive, splash and play together. Numerous stories, especially from the East Slavs, say that the Vili would live by water until the spring when they would move into the wild woods and cultivated fields. Most significantly, however, the Vili, like all fairies, were believed to have been the spirits of young women who had “died before their time” and returned to roam the earth as spirits near where they lived and died.

According to Elizabeth Wayland Barber,

“Dying “before their time” meant specifically that, although these girls were daughters of the ancestral line, they had not yet become mothers. Hence they had no descendants, had not become ancestors of anyone, and thus had no stake in the problems of those who still lived So people could not count on these spirits, unlike those of dead mothers, fathers, and grandparents, to help the family tree, and – worse yet – if they had died disappointed or abused, they surely carried a grudge and might behave spitefully.”[3]

What Wayland Barber speaks of is the female virginity and fertility that was deemed sacred in societies across Europe. It was the social duty of a young woman to stay chaste before her marriage and to be fruitful for her husband and family. If, however, she did not fulfil these duties, whether due to premarital sex, bearing an illegitimate child or a premature death, it was believed that there would be dire consequences for her soul. Women who broke the vows of chastity before marriage were ostracized by society and, if they met an early death, it was believed that they would not ascend into Heaven but would instead be doomed to roam the earth for eternity as an otherworldly spirit who would be a danger to humans. However, the tales are not always so tragic. On another side of the story, young virgins who had died before their time were believed to return as spirits who would act as protectors of nature. These spirits would use their eternal virginity to fertilise crops, fields, and forests, providing the mortals with healthy rations of food.

In other versions, most notably Serbian variants, the Vila shares characteristics with the Valkyrie in that she is a warrior who assists heroes in their quests. Once such legend involves Prince Marko, who was King of Serbia from 1371-1395. According to legend, Marko and the legendary knight Miloš Obilić were riding on horseback through the forest when they encountered the Vila Ravijojla. She became Marko’s blood sister and promised to help him in dire situations, and she fulfilled her promise when she helped him to slay the monostrous three-headed Musa Kesedžija. The legend was later retold as an epic poem Marko Kraljević and the Vila.

For his ghostly brides, Heine seems to have been based them on the Samovila from Bulgarian and Slovak folklore. The Bulgarian Samovili were the spirits of young women who had died unbaptised while the Slovak Samovili were the souls of young brides who had died unmarried and were doomed to roam the earth at night. In Polish folklore, they are the spirits of beautiful, but frivolous young girls, who are eternally condemned to atone for their mischievous lifestyles by floating in the air midway between earth and sky. To those who were kind to them in their lives, they show kindness in return, but to those who wronged them, they show evil. In short, the European legends of fairies revolve around society’s view of women, their sacred virginity and fertility, and the judgement of those who “fell from grace” in the hands of men. Heine’s Wilis are an amalgamation of different variants of the Vila as it was, and still is, very common for writers to write about their own versions of mythological creatures, including borrowing their name and using the German variant.

Victor Hugo’s Fantômes

After he read Heine’s passages, Gautier seized a piece of paper and wrote the words Les Wilis, a ballet. However, his enthusiasm soon faded as he was soon faced by the fear that such a poetic fantasy could not be well adapted for the stage and discarded the paper. Nevertheless, he confided in his friend and fellow writer Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges about his new inspiration, which, in turn, fired up Saint-Georges with enthusiasm and in three days, he produced a new scenario that bore little similarity to Gautier’s original idea. Gautier later admitted:

“Being unversed in the requirements of the theatre, I had been thinking of quite simply setting to action, for the first act, Victor Hugo’s charming “Orientale”. The scene was to be set in a beautiful ballroom belonging to some prince. The chandeliers would be lit, the flowers arranged in the vases, the tables laid, but the guests not yet arrived. The wilis would appear momentarily, attracted by the pleasure of dancing in a room ablaze with crystal and gilding, in the hope of attracting a new recruit. The Queen of the Wilis would touch the floor with her magic wand to inspire the dancers with an insatiable desire for contredanses, waltzes, galops and mazurkas. The entrance of the ladies and gentlemen would make them fly away like insubstantial shadows. Then Giselle, having danced the night through, exhilarated by the enchanted floor and the desire to keep her lover from inviting other women to dance with him, would be surprised by the chill of morning just like the young Spanish girl [of Hugo’s poem], for the Queen of the Wilis, invisible to everyone, would place her icy hand on her heart.”[4]

The second literary work that Gautier is speaking of is the poem Fantômes from Les Orientales by Victor Hugo. The poem tells the story of a fifteen-year-old Spanish girl who loves to dance but dies after a night of frenzied dancing at a ball. The above scenario was his original idea for the first act, but after he read Saint-George’s first act, he decided,

“… we should not have had such a touching and well-acted scene that concludes the first act in its present form, Giselle herself would have been less interesting, and the second act would have lost its element of surprise.”[5]

While his original idea for the first act was very different from the final version, for the second act, Gautier’s original conception was closer to the finalised scenario. But there was one significant difference, which was that it was not a “white act” since it contained an abundance of colour. In continuing to reveal his earlier version, Gautier said,

“At a certain time of year, the wilis gather in a forest glade by the shore of a lake, where large water lilies spread their disc-like leaves over the viscous water that closes in on the drowned dancers. Moonbeams glitter between those black, carved hearts that seem to float like long-dead loves. Midnight chimes, and from every point of the horizon, led by will-o’-the-wisps, come shades of girls who have died at a ball or as a result of dancing. First, with a purring of castanets and a swarming of white butterflies, with a large comb cut out like the interior of a Gothic cathedral, and silhouetted against the moon, comes a cachucha dancer from Seville, a gitana, twisting her hips and wearing finery with cabalistic signs on her skirt – then a Hungarian dancer in a fur bonnet, making the spurs on her boots clatter, as teeth do in the cold – and then a bibiaderi [bayadère] in a costume like Amani’s, a bodice with a sandal-wood satchel, gold lamé trousers, belt, and necklace of mirror-bright mail, bizarre jewellery, rings through her nostrils and bells on her ankles – and then, last of all, timidly coming forward, a petit rat of the Opéra in the practice dress, with a kerchief around her neck and her hands thrust into a little muff. All these costumes, exotic and commonplace, are discoloured and take on a sort of spectral uniformity. The solemn assembly takes place and ends with the scene of the dead girl emerging from her tomb and seeming to come to life again in the passionate embrace of her lover, who is convinced that he can feel her heart beating alongside his.”[6]

The abundance of colour was the inclusion of wilis from different nations – Spain, Hungary, India, France – dressed in discoloured costumers, but this detail was discarded by Saint-Georges in favour of the tradition of all the dancers wearing white, following in the steps of Ballets of the Nuns and La Sylphide, the former being the work in which the so-called “white act” originated. Gautier included the scenario of Giselle in his published dramatic works, but he never neglected to acknowledge and credit Saint-Georges for his contributions since it was Saint-Georges who shaped the libretto into what it became. The scenario of the first act was transferred from a ball in a grand ballroom to a celebration of a grape harvest in a medieval Rhineland village and Giselle became a plucky young peasant girl with a love for dancing who is in love with and betrothed to a disguised nobleman, but she is not aware of his true identity. The scenario of the second act was retained in terms of the location, but now, Heine’s passage on vengeful ghostly brides was brought to life and Giselle, who is drawn into their cult, is given a choice to either take revenge on her lover or to forgive him. The new ballet was to be called Giselle, ou Les Wilis.

Composition and choreography

When their libretto was completed, Gautier and Saint-Georges first showed it to Perrot. Perrot was delighted with the idea, considering it to be much more suitable for Grisi than La Rosière de Gand and took it to Adolphe Adam, who happily agreed to compose the new ballet. Together, the four men persuaded Léon Pillet to postpone La Rosière de Gand in favour of Giselle, ou Les Wilis on the grounds that the former would gain by Grisi’s success in the latter. The creative team were given a deadline to create their new work – May 1841.

Adam got to work on his new composition with much enthusiasm, though, in this case, his enthusiasm seems to have been brought to a whole new level. Working always seemd to stir something in his imagination and the new work soon began to take shape. Adam’s enthusiasm was increased by the fact that he was working with friends, as he expressed in his memoirs:

“I was on terms of a very close friendship with Perrot and Carlotta, and the work took shape, so to speak, in my drawing room.”[7]

Though the score was mostly entirely original, Adam also recycled some music from another of ballet he had composed called Faust, which had been performed in London some years earlier. Perhaps the most interesting feature of Adam’s score is his use of leitmotifs for the main characters, which are heard several times throughout the ballet. The most famous are the love theme of Giselle and Albrecht and the sinister themes of the Wilis. The use of leitmotifs in a ballet score would later be seen again in Ludwig Minkus’s La Bayadère and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. In his memoirs, Adam claimed that it only took him three weeks to complete the score, but this is quite an exaggeration. He was probably referring to the music (melodies and rhythms) because the dates on which he handed in the full completed score show that the orchestration took much longer. According to the records, Act 1 was finished by April, but Act 2 took longer: the beginning was completed by the end of April, the pas de deux on the 30th May and the overture, the remainder of the act and the finale were not completed until early June.

Jules Perrot and Jean Coralli were commissioned as the choreographers of the new ballet, with Perrot choreographing for the principals and soloists and Coralli choreographing for the corps de ballet. The role of Giselle was created especially for Perrot’s muse and lover Carlotta Grisi, the role of Duke Albert (later renamed Albrecht) was created for Lucien Petipa and the role of Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis, was created for the French Prima Ballerina Adèle Dumilâtre. The ballet premièred in Paris on the 28th June 1841 and was a tremendous success.

London première

Nine months later, Giselle was staged in London on the 12th March 1842 at Her Majesty’s Theatre, with Grisi in the titular role. The first London production was produced by the Ballet Master Deshayes with assistance from Perrot and the première was another tremendous success. However, due to the difference in size of Her Majesty’s Theatre to that of the Salle Le Peletieur (the latter was bigger and had more depth), the ballet could not be staged on the same lavish scale as the original Parisian production. In an article for the Courrier de l’Europe, the Vicomtesse de Malleville expressed her disappointment in the London production, stating that certain numbers were cut – the Peasant Pas de deux in the first act was omitted – and dismissed the staging as “an inevitable fiasco”. However skimpy the production may have been to some, however, the enthusiasm the new ballet received in London is undeniable; it was even shared by the British Monarchy. Thirteen performances of Giselle starring Grisi were held in London and among those who attended two of these performances was Queen Victoria. For a ball held at Buckingham Palace in April, the composer Jullien was commissioned to arrange a quadrille, a galop and a waltz based on Adam’s score.

Grisi returned to Paris in April 1843 and the Director of Her Majesty’s Theatre, Benjamin Lumley, planned to stage Giselle again for the following season. However, he was unable to engage Grisi for the 1843-44 season and dreaded the thought of omitting such a popular ballet from the repertoire, so he had to look elsewhere for another ballerina to dance the tragic peasant girl. The ballerina who he successfully engaged was Fanny Elssler, who had recently returned to Europe after her tour of America. This engagement marked not only the return of Giselle to the London stage, but also Elssler’s début in the role. Elssler’s début performance as Giselle took place on the 30th March 1843; this marked the occasion when another great ballerina of the Romantic Era débuted in what is now the most famous Romantic Ballet. Elssler’s portrayal of the role was very different from that of Grisi and reaction to her performance was mixed. The overriding reason for this was because, unlike Grisi, the roles of spiritual, supernatural maidens were not Elssler’s forte, as her talents and abilities were more suitable for the earthly, mortal heroines. Therefore, her performance of the second act lacked that spiritual, otherworldly grace and elegance that the role of Giselle demands, but her performance of the first act was much stronger. Everyone agreed that what Elssler lacked in the second act, she made up for it with what she brought to the first act. Elssler performed in Giselle eight times that season and both she and Grisi would return to London the following season to perform the role again.

Giselle in Russia

Like many Parisian ballets, Giselle did not last in its Parisian or London homes. Perrot and Coralli’s version was performed for the final time at the Paris Opéra in 1868 and it was in Russia that Giselle was given a permanent home. A year after its world première, the ballet was staged in Saint Petersburg for the Imperial Ballet by the Ballet Master Antione Titus on the 30th December [O.S. 18th December] 1842, especially for the definitive Russian Prima Ballerina of the Romantic Era, Elena Andreyanova. Five years later, Petipa arrived in Saint Petersburg, having been appointed Premier Danseur of the Imperial Theatres, and made his début in Titus’s production in the role of Albrecht on the 5th December [O.S. 23rd November] 1847, with Andreyanova in the titular role. The following year, Fanny Elssler arrived in Russia and made her début in Titus’s production on the 22nd October [O.S. 10th October] 1848, with Petipa as Albrecht. Since before his arrival in Russia, Petipa was very familiar with Giselle; not only had his brother Lucien originated in the role of Albrecht, Petipa himself had previously danced the role for his début performance in Bordeaux in 1843 and again in 1844 for his début performance in Madrid. His knowledge of Giselle would prove to be very vital for the ballet’s future and preservation.

Shortly after Elssler’s arrival in the Imperial Russian capital, Perrot arrived in Saint Petersburg as the new Ballet Master of the Imperial Theatres. Among the Parisian ballets that he and other Frenchmen had created, Perrot staged his own Russian production of Giselle and for this staging, he was assisted by Petipa. Perrot revised the choreographic contributions of Coralli for the corps de ballet and although Petipa worked to Perrot’s indications, he also made his own independent touches to the ballet, especially to the dance of the Wilis in the second act. While the staging of the production was in progress, Fanny Elssler was performing in Moscow at the time and was unavailable for more engagements in Saint Petersburg; she gave her last performance in Russia in the winter of 1850. Fittingly as it turned out, the ballerina who would dance Giselle for Perrot’s Russian staging was nonother than the original Giselle herself, Carlotta Grisi, who arrived in Saint Petersburg in the autumn of 1850 and cast in the role of Albrecht was Christian Johansson. Perrot’s Russian staging of Giselle premièred on the 20th October [O.S. 8th October] 1850 at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre. This new Saint Petersburg staging would further secure the preservation of Giselle in the ballet repertoire, but after Perrot’s departure from Russia, it would be Petipa’s revival that became the definitive version of the ballet from which all modern productions derive.

Petipa staged his first revival of Giselle in 1884 for the Prima Ballerina Maria Gorshenkova. For this revival, Ludwig Minkus composed a new pas de deux that Petipa added to the first act for Gorshenkova. This pas de deux did not find a permanent home in the ballet, but the music has survived and it resurfaces now and then when used in ballet galas. Petipa also further elaborated the touches he had made to Perrot’s 1850 staging, expanding the dances into an elaborated Grand Pas des Wilis. Despite the addition of the new pas de deux composed by Minkus, the first act seems to have remained untouched from the Perrot/Coralli version, while the second act was expanded. Petipa’s first revival of Giselle premièred on the 17th February [O.S. 5th February] 1884. He would revive the ballet again four times; his second revival was staged in 1887 for the Italian Prima Ballerina Emma Bessone. He revived the ballet for a third time in 1889 for Elena Cornalba and again in 1899 for Henriëtta Grimaldi. In 1903, Petipa staged his final and most important revival for the young Anna Pavlova, which premièred on the 13th May [O.S. 30th April] 1903 at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre. Petipa himself coached Pavlova for the role and with her remarkable jumps, abandon and soulfulness, Pavlova set a new standard for Giselle. The ageing Petipa must have seen in this remarkable artist the embodiment of the Romantic ballerinas he had known and admired in his youth.

Petipa’s final revival of Giselle was notated in the Stepanov notation method; the second act was notated in 1899 and the first act was notated in 1903 during the rehearsals in which Petipa was coaching Pavlova in the title role. The notation scores are part of the Sergeyev Collection. The Parisian version of the ballet was also notated in the 1860s by Henri Justamant.

Giselle in the 20th century

Giselle was apparently Pavlova’s favourite ballet and she would be one of three great interpreters of the titular role in the early twentieth century. She first performed in the ballet in the west in Warsaw in 1904. In 1908 and 1909, a troupe of dancers from the Imperial Ballet led by Pavlova, Nikolai Legat and Alexander Shiryaev included Giselle in their tour of the Baltic States, Scandinavia and Germany. Pavlova went onto dance in Giselle with her company many times on her global tours, performing in the ballet in such places as Vienna, the USA, London, Chile and Argentina. Among those who saw Pavlova as Giselle was Dame Alicia Markova, who would later go onto to become another great Giselle in her own right.

After Pavlova, the second great interpreter of the epoch was Tamara Karsavina, who débuted as Giselle in Prague on the 24th April 1909. Karsavina later made her Saint Petersburg début in the role on the 8th October [O.S. 26th September] 1910, with Samuil Andrianov as Albrecht. There were other ballerinas of the Imperial Ballet who attempted the role of Giselle at the time, but, unlike Pavlova and Karsavina, they were not very successful. Matilda Kschessinskaya made her début as Giselle in 1916 when she was 44 years old and it was one of the final roles that she ever danced in Russia. Once in Saint Petersburg, one of Karsavina’s planned performances as Giselle was given instead to Agrippina Vaganova at the last minute, which greatly peeved Karsavina since the ballet was one of her favourites and she considered Vaganova to be unsuitable for the role. Much to her delight, however, Karsavina said that Vaganova’s performance was a “complete disaster”.

Ten years after Karsavina’s début as Giselle, the third great interpreter of the role finally came to light and that artist was the Prima Ballerina Olga Spessivtseva, who many agree was the supreme Giselle of the twentieth century. Spessivtseva was taught and coached for the role by Nikolai Legat and made her début in Petrograd on the 30th March 1919, with Pierre Vladimirov as Albrecht. Among those who saw Spessivtseva as Giselle and was greatly inspired by her performance was Galina Ulanova. Ulanova would go onto become another great interpreter of Giselle and when she danced the role in London as part of the Bolshoi Ballet’s first tour of the west in 1956, she asked Sir Anton Dolin how her performance of Giselle, especially in the first act, compared to that of Spessivtseva.

In 1910, Giselle made its return to Paris after a forty-two year absence when Sergei Diaghilev staged Petipa’s revival for the Ballet Russes. Diaghilev’s staging included choreographic revisions by Mikhail Fokine and decors and costumes by Alexandre Benois. Diaghilev’s revival of Giselle premièred on the 17th June 1910 at the Théâtre National de l’Opéra, with Tamara Karsavina as Giselle and Vaslav Nijinsky as Albrecht. Since then, Giselle has been a prominent member of the repertoires of ballet companies all over the world, staged in various productions. Some of the most famous modern productions include those by Sir Peter Wright for the Royal Ballet, the Birmingham Royal Ballet and the Bayerisches Staatsballett, Yuri Grigorovich for the Bolshoi Ballet and Yvette Chauviré for La Scala Ballet. In 1942, Nikolai Sergeyev staged the ballet for Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet, staging the choreography from the Imperial Ballet production from his notation scores. The 20th century also produced many more great interpreters of the titular role, including Alicia Alonso, Dame Margot Fonteyn, Yvette Chauviré, Natalia Makarova and Carla Fracci.

In 2019, Alexei Ratmansky staged a new production of Giselle for the Bolshoi Ballet that is based primarily on the Sergeyev notation scores, but also uses details from the Justamant notations scores. Ratmansky’s production of Giselle premièred on the 21st November 2019 at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, with Olga Smirnova as Giselle, Artemy Belyakov as Albrecht, Eric Svolkin as Hilarion and Angelina Vlashinets as Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis.

An interesting fact about the passing down of Giselle from generation to generation is that the scenario underwent changes that have made modern productions differ quite vastly from the productions of the 19th century. Perhaps the biggest deviations from the 19th century productions is the presentation of some of the characters, though it always depends on the production. Some productions portray Albrecht as deceitful and haughty, who is only toying with Giselle, while others portray him as warm-hearted and loving, who is genuinely in love with the peasant girl, despite his betrothal to Bathilde, another character whose portrayal has underwent change. In some productions, Bathilde is portrayed as cold and cruel, while in others, she is kind and gentle and another character whose portrayal differs is Hilarion; some productions portray him in a somewhat heroic light, while in others, he is Albrecht’s bitterly jealous rival.

The portrayal of these characters in the 19th century productions is as follows – Albrecht is a good-hearted, caring nobleman, who is madly in love with a peasant girl, despite his betrothal and their differences in social ranks; his relationship with Giselle is one of genuine love and affection, not a careless and selfish seduction. Bathilde is a kind and gentle noblewoman, who is drawn to Giselle and mourns for the peasant girl when she dies. Hilarion is the local forester, who, from the very beginning, is bitterly jealous of Albrecht and Giselle’s love and his jealousy leads him to ruining Giselle’s happiness when he discovers Albrecht’s true identity, but his actions ultimately result in her death. The changes made to these characters occurred during the 20th century, especially in Russia where the roles of the aristocrats became villains and the peasants became heroes; in the love triangle between Giselle, Albrecht and Hilarion, the roles of the two men were switched – Albrecht became the villain and Hilarion became the hero. As described by Yuri Slonimsky, this switch was ideologically driven by the Soviet ideology that glorified the peasants and demonised the aristocracy. However, the switch only proved to be illogical since Hilarion remained the one to die at the hands of the Wilis, while Albrecht was still forgiven and rescued.

There have also been significant changes made to certain moments in the story, with the most distinctive being the opening sequence, the cause of Giselle’s death and the ending. The standard opening sequence with the meeting between Giselle and Albrecht shows Albrecht knocking on Giselle’s door, after which, she emerges from her cottage and he seduces her with his flirtations and declarations of love. In the 19th century productions, however, when the ballet begins, Giselle and Albrecht are already a couple; Albrecht knocks on Giselle’s door and when she emerges, she embraces him. Then she tells him that the previous night, she dreamt of him falling in love with another woman and he comforts her by reassuring her of his love. It is not certain when the love scene of the first act was changed to the scenario widely used today, but it seems to have been sometime in the early 20th century.

The cause of Giselle’s death varies in different productions; in some, she suffers from a weak heart and when she goes mad, her heart finally gives out and she dies; in other productions, especially in Sir Peter Wright’s production, she kills herself with Albrecht’s sword, which is given as the reason for why she is buried in the forest in non-consecrated ground. In the 19th century scenario, there is no suicide, but rather an attempted suicide – Giselle tries to stab herself with Albrecht’s sword, but does not succeed when Albrecht stops her and takes the sword from her. This is another distinctive change in modern productions, since today, it is usually Hilarion who stops Giselle from stabbing herself, though in Gautier’s original libretto, it was her mother Berthe who stopped her. As Alexei Ratmansky explained, the music for the scene does not suggest suicide and Giselle dies of a broken heart, implying that she has danced herself to death. The curtain falls on everyone surrounding her lifeless body and mourning her, including Albrecht, Berthe, Hilarion and Bathilde. Giselle is buried in the forest rather a consecrated graveyard because, as was commonly believed at the time period in which the story is set, everyone believes that she was possessed by an unholy spirit, which caused her descend into madness, therefore making it inappropriate for her to be buried in a Christian grave.

Another interesting change is the ending. Many modern productions end with Giselle disappearing or returning to her grave after bidding farewell to Albrecht, who is left sorrowing and alone. The scenario of the 19th century productions, however, presented a different ending that some modern productions have restored. After the Wilis are forced to disappear when dawn breaks, Giselle comforts Albrecht one last time and he carries her to a flowery mound. As she disappears, Bathilde and her retinue arrive looking for Albrecht and Giselle tells him that he should marry Bathilde. Albrecht is grief-stricken, but the last wish of his beloved Giselle is sacred. After she has gone, he picks some flowers from the mound and kisses them, takes a few small steps towards Bathilde and the courtiers and collapses into their arms, with his hands reaching out to Bathilde, who reaches back. This ending is parallel to the ending of the first act when the peasants crowd around Giselle’s body. It seems, however, that by 1899, Petipa was using a different ending because in the ending recorded in the 1899 Sergeyev notation scores, after Giselle disappears, Albrecht collapses and dies suddenly and his body is then found by his squire Wilfred and four male courtiers. This is the ending that was used in the 1930s production of Giselle that was danced by the Vic-Wells Ballet and was also apparently used in Anna Pavlova’s production.

Pas seul

The Pas seul is the famous variation for Giselle in the first act that is retained in many modern productions. This variation was composed by Riccardo Drigo in 1887, though the music is usually mistakenly credited to Ludwig Minkus, as Adam Lopez has discovered. It was composed for Elena Cornalba for her performance in Fiametta in 1887 and she must have transferred it into the first act of Giselle when Petipa revived the ballet for her that same year. Unlike the other signature pieces created and added for various ballerinas before, the Pas seul found a permanent home in the Imperial Ballet repertoire and was performed by the ballerinas who succeeded Cornalba in the role of Giselle. The variation was first introduced to the west by Olga Spessivtseva when she performed it at the Paris Opéra in 1924. The Pas seul’s popularity with ballerinas, however, had its cost as the original variation was forgotten. Tamara Karsavina was the last ballerina to have opted for the original, but alas, her performance as Giselle was never recorded.

Peasant Pas de deux

The Peasant Pas de deux is another of the most famous passages in Giselle and has an interesting history. Before the 1841 Paris première, one of the Paris Opèra ballerinas, Nathalie Fitz-James was determined to have her own pas in Giselle. Like many of her colleagues, Fitz-James was a mistress of one of the Opèra’s most influential patrons and used her relationship with him to influence the arrangement of a new pas to be added for her. However, Adolphe Adam was unavailable at the time to compose more music, so Jean Coralli had to look elsewhere. In the end, he arranged a new pas de deux for Fitz-James to music by the German composer, Friedrich Burgmüller from his suite Souvenirs de Ratisbonne. The new pas was later christened as the Pas des paysans (aka Peasant Pas de deux); it was first performed by Fitz-James and the danseur, Auguste Mabille and has remained in Giselle ever since.

In Petipa’s time, the Peasant Pas de deux was performed by the likes of Tamara Karsavina, Mikhail Fokine and Vaslav Nijinsky. The Sergeyev Collection includes notation scores for the pas de deux when it was performed by Agrippina Vaganova and Mikhail Obukhov. In most modern productions, the Peasant Pas de deux is performed by at least six dancers, which is not its original concept or how it was staged by Petipa.

Sources

- Petipa, Marius (1971) Мариус Петипа. Материалы. Воспоминания. Статьи. Marius Petipa. Materials, Recollections, Articles. Leningrad: Iskusstvo (Искусство) A. Art

- Meisner, Nadine (2019) Marius Petipa, The Emperor’s Ballet Master. New York City, US: Oxford University Press

- Ashton, Geoffrey (1985) Giselle. Woodbury, New York: Barron’s

- Balanchine, George (1979) 101 Stories of the Great Ballets. New York: Anchor Books

- Beaumont, Cyril (1937) Complete Book of Ballets. London, UK: Putnam

- Beaumont, Cyril (1944) The Ballet Called Giselle. London, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Guest, Ivor (1983) Cesare Pugni: A Plea For Justice. London, UK: Dance Research Journal. Vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 30-38

- Guest, Ivor (1985) Jules Perrot: Master of the Romantic Ballet. London, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Guest, Ivor (2008) The Romantic Ballet in Paris. Alton, Hampshire: Dance Books Ltd

- Inglesby, Mona and Hunter, Kay (2008) Ballet in the Blitz: the History of a Ballet Company. Debenham, Suffolk, England, UK: Groundnut Publishing

- Kant, Marion/Various (2007) The Cambridge Companion to Ballet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Kschessinskaya, Matilda, H.S.H. The Princess Romanovsky-Krassinsky (1960) Dancing in Petersburg: The Memoirs of Mathilde Kschessinskaya. Alton, Hampshire: Dance Books Ltd

- Kirstein, Lincoln (1984) Four Centuries of Ballet: Fifty Masterworks. New York: Dover

- Legat, Nikolai (1939) Ballet Russe: Memoirs of Nikolai Legat. London, UK: Methuen

- Letellier, Robert Ignatius (2008) The Ballets of Ludwig Minkus. Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Footnotes

[1] Quoted in Ivor Guest’s The Romantic Ballet in Paris, p. 345

[2] Quoted in Heinrich Heine’s L’Allemagne, published in 1835

[3] From The Dancing Goddesses by Elizabeth Wayland Barber, p. 18

[4] Quoted in The Romantic Ballet in Paris by Ivor Guest, p. 345-346

[5] Quoted in The Romantic Ballet in Paris by Ivor Guest, p. 346

[6] Quoted in The Romantic Ballet in Paris by Ivor Guest, p. 346

[7] Memoirs of Adolphe Adam

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.