Romantic Ballet in four acts and five scenes

Music by Cesare Pugni & Riccardo Drigo

Libretto by Jules Perrot and Benjamin Lumley

1886 décor by Ivan Andreev (Act 1) and Heinrich Levogt (Act 3 and Act 4, scenes 1 and 2)

1899 décor by Leonid Andreev and Orest Allegri (Act 1), Vasilii Shiriaev (Act 2), Gavriel Kamensky and Grigori Iakovlev (Act 3), Sergei Vorobev (Act 4, scene 1) and Orest Allegri (Act 4, scene 2)

World Première

9th March 1844

Her Majesty’s Theatre, London

Choreography by Jules Perrot

Original 1844 Cast

Esmeralda

Carlotta Grisi

Phoebus de Châteaupers

Arthur Saint-Léon

Pierre Gringoire

Jules Perrot

Fleur-de-Lys

Adélaïde Frassi

Quasimodo

Antoine Louis Coulon

Saint Petersburg Première

2nd January 1849 [O.S. 21st December 1848]

Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre

Original 1848/49 Cast

Esmeralda

Fanny Elssler

Phoebus de Châteaupers

Pierre Frédéric Malevergne

Pierre Gringoire

Jules Perrot

Fleur-de-Lys

Tatiana Smirnova

Claude Frollo

Nikolai Golts

Première of Petipa’s first revival

29th December [O.S. 17th December] 1886

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1886 Cast

Esmeralda

Virginia Zucchi

Phoebus de Châteaupers

Iosif Kschessinsky

Pierre Gringoire

Pavel Gerdt

Quasimodo

Alfred Bekefi

Claude Frollo

Felix Kschessinsky

Première of Petipa’s final revival

3rd December [O.S. 21st November] 1899

Imperial Mariinsky Theatre

Original 1899 Cast

Esmeralda

Matilda Kschessinskaya

Phoebus de Châteaupers

Iosif Kchessinsky

Pierre Gringoire

Pavel Gerdt

Fleur-de-Lys

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

Quasimodo

Alfred Bekefi

Claude Frollo

Nikolai Aistov

Plot

The beautiful gypsy girl, Esmeralda, under gypsy law, “marries” the poet, Pierre Gringoire to save him from execution in the hands of the Gypsy King. The groom is smitten, but Esmeralda makes it clear that the marriage is strictly one of convenience. However, there is another who desires the gypsy girl – the corrupt Archdeacon Claude Frollo, who is torn between his duty to God and his lustful obsession with Esmeralda. When Frollo orders his deformed henchman, Quasimodo to capture Esmeralda, she is rescued by the handsome Captain Phoebus de Châteaupers and falls in love with him, unaware that he is engaged to the beautiful Fleur-de-Lys. Rather than have her attacker arrested, Esmeralda shows Quasimodo mercy and gives him some water, earning his affections. Phoebus gives Esmeralda his fiancée’s scarf, but when Fleur-de-Lys discovers this, she angrily calls off the engagement, leaving Phoebus free to be with Esmeralda. However, the jealous Frollo attempts to exact revenge by stabbing Phoebus, believing he has killed him, and frames Esmeralda for the crime. Esmeralda is found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging. On the day of the Feast of Fools, she is led to the gallows as Frollo watches in triumph. However, his plot is thwarted when Phoebus arrives alive and well, having survived the stabbing and recovered from his wound, and clears Esmeralda’s name.

History

La Esmeralda was created by Jules Perrot and Cesare Pugni for the Ballet of Her Majesty’s Theatre in London and is based on the famous novel Notre-Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo. After its successful publication in 1831, Hugo’s novel was first adapted to the stage in an opera by his friend, the French composer Louise Bertin in 1836 under the title La Esmeralda, shifting the emphasis of the gothic architecture of the great cathedral to the plot surrounding the lead female character, and the libretto was written by Hugo himself in which he made drastic changes that reduced the vast panorama of his novel to the dimensions of an opera libretto. Bertin’s La Esmeralda premièred on the 14th November 1836 at the Paris Opéra. However, the opera was not a success, but its libretto was printed and ultimately gave way to the story that would be told in subsequent opera and ballet adaptations of Hugo’s novel. The novel was first adapted into a ballet at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan by Antonio Monticini in 1839, who based his version on Hugo’s libretto for Bertin’s opera. Monticini’s version differed greatly from Perrot’s, primarily due to a common tradition in Italian ballets at the time, where the functions of mime and dance were separated – the principal roles were played by mimes, while Fanny Cerrito, who was Prima Ballerina of La Scala at the time, only appeared in the dances. Hugo’s opera libretto was later used again by the Russian composer Alexander Dargomynsky for his opera Esmeralda opera that was staged in Moscow in 1847 and then in Saint Petersburg in 1851 and was a great success.

Creation of Jules Perrot’s La Esmeralda

In 1843, Perrot was commissioned as choreographer for the 1843 London season at Her Majesty’s Theatre by its director Benjamin Lumley and it was during this season that he formed his collaboration with Cesare Pugni. It was Lumley’s idea for a new ballet adaptation of Hugo’s novel for the upcoming season, but when he suggested it to Perrot, the latter rejected the idea as impracticable since it was a hard novel to reduce into a ballet libretto. Nevertheless, Lumley was persistent and eventually succeeded in persuading Perrot that it was a subject of good artistic value and potential. Following Hugo’s work with Bertin’s opera, Lumley, Perrot and Pugni got to work in producing the libretto, which proved to be no easy task and Perrot was more than grateful for Lumley’s help. Lumley wrote of the experience:

I frequently sat up with him the greater part of the night in order to assist and encourage him in his labours. [Pugni] was always present ready to seize any idea that might suggest itself for a ‘situation’ or a ‘pas’[1]

The plan was for La Esmeralda to be completed and produced within a month, but that proved over-sanguine as several circumstances caused for the ballet to be deferred until the following season. One such circumstance was that Perrot had initially hoped to engage Fanny Elssler for the London season, but when it seemed she was unavailable, he instead brought Adèle Dumilâtre, who had created the role of the Queen of the Wilis in Giselle. The new ballet was to be created for the young French ballerina, but then they received word that Elssler was available after all and soon arrived in London. Anther circumstance was that Perrot was then injured during a performance, forcing him off-stage for a while, but he was able to coach Elssler for her performances as Giselle. La Esmeralda was put on hold, but Perrot enjoyed a successful season in London, especially with the creation of Ondine, ou la Naïade in June of that year.

In February 1844, after some time abroad, Perrot returned to London and could hardly wait to begin work on La Esmeralda, which had been frequently on his mind for nearly a year. The initial doubts he had expressed to Lumley regarding the ballet were now gone and he had read and re-read Hugo’s novel, absorbing its powerful narrative until the characters had become as real as if he had known them in the flesh.[2] Now, he saw all too clearly how they should be presented on stage. The dramatic events surrounding the gypsy Esmeralda had already taken shape in Perrot’s imagination as one-act ballet made up of a sequence of powerful and vivid scenes that depicted certain episodes from the novel – Esmeralda’s gypsy “marriage” to Pierre Gringoire, her attempted abduction in the hands of Quasimodo at the orders of Claude Frollo, the love triangle involving Esmeralda, the captain Phoebus and his fiancée Fleur-de-Lys and Frollo framing Esmeralda for Phoebus’s attempted murder, for which she is wrongfully sentenced to death. The resulting libretto was one that followed the novel and Hugo’s libretto for Bertin’s opera, though Perrot could not have seen the opera since he was in Vienna when it had its handful of performances at the Paris Opéra, and he was in Naples when Monticini’s ballet premièred in Milan. Nevertheless, it appears that Perrot and Lumley could have worked from both Hugo’s novel and his opera libretto, but the aim appeared to be to strengthen the weaknesses of the earlier opera and ballet libretti. One significant difference between Perrot and Lumley’s libretto and the earlier two was the restoration of Pierre Gringoire, who was not featured in the earlier versions. Another difference was a change Hugo had made, which was the transformation of Captain Phoebus from a callous, vain womaniser into a noble hero who does not lust Esmeralda but falls genuinely in love with her and appears in the nick of time to rescue her from the gallows and clear her name. Hugo, however, kept the element of tragedy in the ending as in his libretto, Phoebus has been mortally wounded and after rescuing her, dies in Esmeralda’s arms. It is possible that Perrot may have wished to retain the original tragic ending of the novel in which Esmeralda is hanged, but it seems that he had to bow down to the pressures of public taste and give the ballet a happy ending, for there was only so much realism that the audience of that time could take.

When the casting was decided, the role of Esmeralda was not given to Perrot’s first choice, Fanny Elssler or Adèle Dumilâatre, but to his former muse and lover Carlotta Grisi, who Lumley succeeded in engaging at Her Majesty’s Theatre for the 1844 season. Cast in the role of Phoebus de Châteaupers was the 23-year-old Arthur Saint-Léon, who at the time was one of the most renowned Premier Danseurs in Europe, and Perrot himself originated the role of Pierre Gringoire. The role of Fleur-de-Lys, Phoebus’s fiancée was originated by a young ballerina from Florence, Adelaide Frassi, with this being her London début. Cast as Quasimodo was Anton Louis Coulon and the role of Claude Frollo was given to Louis Gosselin.

La Esmeralda premièred on the 9th March 1844. The ballet was a huge success, with many praising Grisi’s performance in the title role. When she had to return to Paris to perform in Giselle on the 6th May, Grisi performed in La Esmeralda for her benefit performance at Her Majesty’s Theatre. Following Grisi’s departure, La Esmeralda was temporarily removed from the repertoire until it was revived in the last weeks of the season for Fanny Elssler, whose performances as the gypsy girl, with her own distinctive interpretation, were a huge success in their own right. Elssler later danced as Esmeralda in Milan when Perrot staged the ballet at the Teatro alla Scala a few months after its world première.

La Esmeralda in Russia

Like many western ballets created at the time, La Esmeralda eventually disappeared from the London repertoire; it was performed for the final time at Her Majesty’s Theatre in 1857. It was only when the ballet was brought to Russia that it found a permanent home. In 1848, when Fanny Elssler arrived in Russia, among the ballets that were staged for her in Saint Petersburg was La Esmeralda (staged under the title Esmeralda in Russia), which she requested for her benefit performance. However, Perrot had not yet arrived in the Imperial Russian capital, not in the least due to the difficulties that came with engaging both him and Elssler. Therefore, Elssler took up the task of staging the ballet herself and directing the rehearsals and Petipa was engaged as her assistant until Perrot’s arrival. In his memoirs, Petipa wrote the following account on this event:

While I was in Moscow, Fanny Elssler was invited to Saint Petersburg, and started to rehearse the ballet Esmeralda… On my return from Moscow, I immediately commenced the staging of this ballet. I had finished the first act when Jules Perrot, the author of the ballet, arrived and himself took over the production of his wonderful work.

Afterwards, I always adhered to the recommendations and traditions of the author, neither permitting myself the smallest deviation, nor interpolating such disgusting tricks as the breaking of Quasimodo’s jaw during the already heartrending scene with Esmeralda’ mother, which for some reason was permitted on the Moscow stage.” – Russian Ballet Master: The Memoirs of Marius Petipa (p. 31)

Just like with most of the ballets he brought to Russia, Perrot was required to make drastic changes to Esmeralda so that it would fit the Russian audience’s expectations of a ballet production, for in Russia, a ballet was expected to fill an entire evening. Pugni was called in to extensively revise and expand his score and the original one-act and five-tableaux staging of Esmeralda was expanded to three acts and five tableaux.

Perrot’s revival of Esmeralda premièred on the 2nd January 1849 [O.S. 21st December 1848] at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, with Elssler as Esmeralda, Pierre Frédéric Malevergne as Phoebus (renamed “Feb” in Russia and a role that Petipa would later take over and dance with Elssler), Perrot as Pierre Gringoire, Tatiana Smirnova as Fleur-de-Lys and Nikolai Golts as Claude Frollo. The ballet was a huge success, with Elssler captivating the Russian audiences with her “fire, vivacity, animation, splendour, and attractiveness.” Petipa wrote of Elssler in his memoirs:

Every balletomane knows what a success this ballet enjoyed; and how could it not be otherwise, when the principal role was played by such a great artist as Fanny Elssler? She was positively inimitable in this role, and all the Esmeraldas I saw afterwards seemed pallid copies. – Russian Ballet Master: The Memoirs of Marius Petipa (p. 31)

Petipa’s revivals

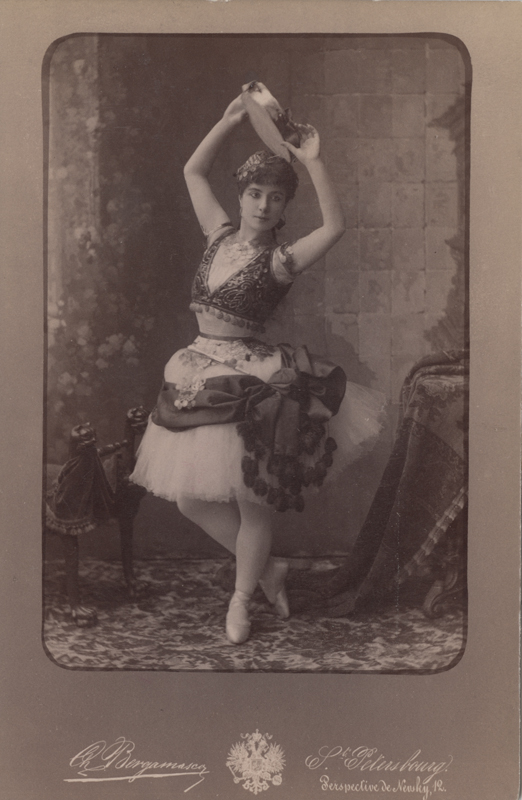

After Perrot’s departure from Saint Petersburg, Petipa had been making his own additions to Esmeralda since 1866. That same year, he added a new pas de deux for the Italian ballerina Claudina Cucchi, which was of such originality that it became known as the Pas Cucchi. In the early 1870s, he arranged a new pas de six for Eugenia Sokolova and in 1872, he inserted a new pas de cinq for Adèle Granztow. That same year, after Grantzow’s departure, Esmeralda disappeared from the Imperial Ballet repertoire. Fourteen years later, it reappeared on the Imperial stage in 1886 when Petipa revived the ballet for the great Virginia Zucchi. It was Petipa’s revival that became the definitive version of the ballet.

After her successful début with the Imperial Ballet in 1885, Zucchi signed her second contract in January 1886, which gave her twenty-four performances for four months. It was announced that Esmeralda was one of two ballets that was to be revived for her (the other was Excelsior). New decors and costumes were crafted, Petipa revised the choreography, Riccardo Drigo was commissioned to revise and refurbish Pugni’s old score and the ballet was expanded from three acts to four acts. Among Petipa and Drigo’s new changes were the additions of a new pas de six for Zucchi and Drigo’s revival of Pugni’s original Grand Pas des fleurs performed by Fleur-de-Lys and Phoebus in the third act. Drigo revised the Grand Pas des fleurs into a Grand Pas Classique, for which he composed some new musical additions. Every balletomane in Saint Petersburg was very excited for this new revival, especially at the thought of Zucchi performing the titular role. The role of Esmeralda makes not only technical demands, but also demands strong dramatic/acting abilities. Zucchi was renowned not just for her virtuosa abilities as a dancer, but also for her incredible dramatic abilities as an actress and every balletomane was convinced that Esmeralda would be only too fitting a role for her.

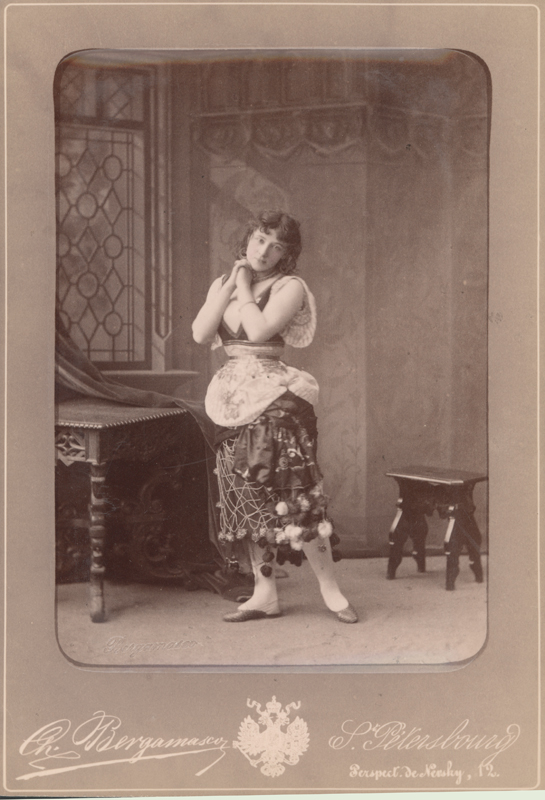

Virginia Zucchi as Esmeralda (1886)

Petipa’s first revival of Esmeralda premièred on the 29th December [O.S. 17th December] 1886 at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre for Zucchi’s benefit performance and reports state that “the theatre was absolutely full.” The revival was an enormous success, with Zucchi’s performance receiving such enthusiastic praise. The critic Skalkovsky wrote, in the words of Zucchi’s biographer Ivor Guest, that “her success that evening was a triumph not merely for herself but also for the art of mime itself,” with Skalkovsky writing, “The shade of Noverre must have surely rejoiced in the Elysian fields.” His fellow critic Pleshcheyev wrote that not even Fanny Elssler could have surpassed Zucchi. Eye witness accounts also state that Zucchi was so in character that she went as far as to shed real tears during the ballet’s most emotional and tragic moments, such as when Esmeralda is being led to her execution in the final act. Zucchi’s performances as Esmeralda became legendary in Russia and the role became among the most coveted of parts for her.

Among those who saw Zucchi perform Esmeralda was the 14 year old Matilda Kschessinskaya, who wrote the following account in her memoirs of how much of an inspiration the Italian ballerina was to her:

I was fourteen when the famous Virginia Zucchi arrived in St. Petersburg. I was already receiving small roles which I strove to interpret to the best of my powers and which even won me praises. But I had no faith in what was being done in our company, and my dancing yielded me no deep satisfaction. I was seized with doubts: had I chosen the career which suited me? I cannot imagine where all that might have led me, had it not been for Virginia Zucchi’s arrival, who, immediately, and radically, altered my state of mind, revealing to me the true meaning of our art. Virginia Zucchi was no longer young, but her exceptional gifts had not lost their vigour. I felt an overwhelming, unforgettable sensation when I watched her. I felt that I was beginning to understand, for the first time, how one should dance in order to deserve the title of a great dancer. Virginia Zucchi had a wonderful gift for mime. She gave all the movements of classical ballet extraordinary charm and astonishing beauty of expression, filling the audience with enthusiasm whenever she danced.

Her acting henceforth became true art for me, and I understood that the essence of such art does not lie exclusively in technique, far from being an end, it is only a means.” – Dancing in Petersburg: The Memoirs of Mathilde Kschessinska (p. 26)

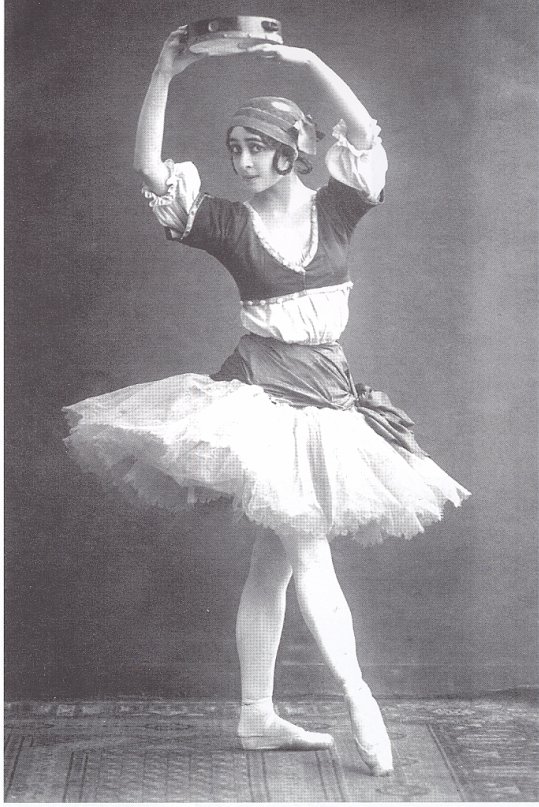

Kschessinskaya would later go on to become another great interpreter of the role of Esmeralda in her own right. In 1899, Petipa added his final touches to Esmeralda when he revived the ballet for the second and final time for Kschessinskaya. The role of Esmeralda was one that Kschessinskaya had always wanted to dance, ever since she saw Zucchi performing the role and was one of her favourites. She had first asked Petipa to allow her to dance the role when she was 20 years old, but Petipa denied her request. Kschessinskaya gives the following account of this conversation in her memoirs:

I told him that I should like to dance Esmeralda. He listened carefully and asked me point-blank in his jargon, “You love?”

Confused, I answered that I was indeed in love, that I did love.

Whereupon he continued, “You suffer?”

I thought it a strange question, and immediately replied, “Certainly not!”

Then he explained to me – a fact which I was to remember later – that only artists who had known the sufferings of love could understand and interpret the role of Esmeralda. – Dancing in Petersburg: The Memoirs of Mathilde Kschessinska (p. 45)

Zucchi had experienced heartbreak with her first love, something that ironically, Kschessinskaya would later experience. However, it could be that the real reason Petipa told her this was that he simply trying to avoid giving Kschessinskaya the role as much as possible, but it was not something he could avoid permanently.

Petipa’s revival of Esmeralda began to be notated in the Stepanov notation method circa. 1900 by Nikolai Sergeyev and his assistants. The notation was created over time while some legendary dancers were rehearsing the ballet: Matilda Kschessinskaya, Sergei Legat, Vaslav Nijinsky, Tamara Karsavina, Agrippina Vaganova, Elsa Vill, Mikhail Fokine, Mikhail Obukhov and Lyubov Egorova are all listed on the notation scores. Kschessinskaya assisted Sergeyev in completing the notation after her retirement in Paris and she is credited on the some of the pages as “Mathilde Kschessinska, Paris, 1923”. The notation scores for Esmeralda are part of the Sergeyev Collection.

Esmeralda in the 20th Century

Alongside Grisi, Elssler, Zucchi and Kschessinskaya, another great interpretor of the role of Esmeralda was Olga Spessivtseva, who made her début in the role on the 24th November 1918. Her biographer Sir Anton Dolin writes that Spessvitseva’s talent “shone like a blazing light.” He then goes on to explain that it was said that at that time, Spessivtseva had embarked on a love affair that had not ended happily, which served as the base for her own interpretation of Esmeralda and made her portrayal, in Dolin’s words, “an interpretation of overwhelming power and pathos.” Before she débuted as Giselle the following year, all agreed that, at that point in time, Esmeralda was Spessivtseva’s greatest role.

In 1902, Alexander Gorsky created his own Esmeralda ballet that was composed by Anton Simon and entitled Gudule’s Daughter for the Imperial Bolshoi Ballet. On the 9th February 1914, Esmeralda was staged for the benefit performance of Nikolai Legat, celebrating his 25th year of service to the Imperial Theatres. For this benefit performance, he chose to dance the role of Pierre Gringoire in Esmeralda because it was his favourite ballet. When he made his entrance in the first act, he received an ovation that lasted at least ten minutes. This was the final time that Legat performed in his favourite ballet at his beloved Imperial Mariinsky Theatre.

After the 1917 revolution, Esmeralda reappeared on the former Imperial Mariinsky stage in 1935 in a new revival by Agrippina Vaganova, which was staged especially for the ballerina Tatiana Vecheslova. Many of Vaganova’s choreographic revisions became the standard choreography for the ballet in subsequent modern revivals. Perhaps the most famous fact about Vaganova’s revival is that it was in this production that the so-called Diana and Actaeon Pas de deux made its première. This was Vaganova’s new revised version of Petipa’s original Pas de Diane from Le Roi Candaule, which she transferred into Esmeralda as a showpiece for Galina Ulanova and Vakhtang Chabukiani. During the Second World War, the Kirov/Mariinsky Ballet evacuated to Perm, but one ballerina who did not evacuate was Olga Iordan. Rebelling against Vaganova, Iordan staged a short-lived production of Esmeralda at the Comedy Theatre in Saint Petersburg that was closer to Petipa’s revival. Due to the many circumstances, however, this production faced multiple problems – the stage of the Comedy Theatre was too small to fit a large ensemble and the production was devoid of male dancers, since they were either in Perm or serving at the front. In 1950, Soviet Ballet Master Vladimir Bourmeister staged his own revival of Esmeralda, which followed Vaganova’s revival, for the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theatre. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Bourmeister’s version is that instead of using the happy ending introduced by Perrot and retained by Petipa, he restored the original tragic ending by Victor Hugo. In Bourmeister’s version, Frollo successfully kills Phoebus, Esmeralda is led to the gallows and the curtain closes with everyone bowing their heads in sorrow when she is hanged for the crime she did not commit.

Throughout the twentieth century, Esmeralda was rarely performed in the west. In his Spessivtseva biography, Sir Anton Dolin inaccurately writes that Anna Pavlova danced her own shortened version of Esmeralda, but he was perhaps referring to her ballet Amarilla. The plot of Amarilla was very similar to that of Esmeralda – Amarilla, a gypsy girl, is in love with a nobleman, who is engaged to a countess and at one point, just like Esmeralda, Amarilla has to dance before her beloved and his fiancée. Amarilla, however, did not use any of Pugni’s music, but was instead set to a pastiche arrangement of music by Drigo, Alexander Glazunov and Dargomizhsky. The ballet was choreographed by Ivan Clustine and premièred in London in 1912. In 1954, Nicholas Beriosov (father of the famous Prima Ballerina Svetlana Beriosova) staged a new full-length production of Esmeralda for the London Festival Ballet (now the English National Ballet). The production starred Natalie Krassovska as Esmeralda, John Gilpin as Pierre Gringoire, Oleg Briansky as Phoebus de Châteaupers and Sir Anton Dolin as Claude Frollo. However, the production was not a success and was mercilessly panned by critics and balletomanes alike. Subsequently, it did not live long in the London repertoire.

Today, Esmeralda is only staged as a full-length ballet in Russia and New Jersey, where it was first staged in 2004. Russian companies that dance the full-length work include the Kremlin Ballet and the Stanislavsky Ballet, both of whom dance in revivals of Bourmeister’s 1950 production. In 2009, Yuri Burlaka and Vasily Medvedev staged a revival of Esmeralda that is largely based on Petipa’s 1899 revival for the Bolshoi Ballet.

Pas de Jalousie (aka La Esmeralda Pas de six)

The most famous passage from Esmeralda is the Pas de Jalousie (commonly known today as the La Esmeralda Pas de six), which was created by Petipa and Drigo for Virginia Zucchi in Petipa’s 1886 revival. As was the custom of the time, a novelty piece was added to showcase the ballerina’s dramatic gifts and the result was a pas de six in the third act entitled the Pas de Jalousie, which replaced Perrot and Pugni’s original pas d’action. In the Pas de Jalousie, Esmeralda and her friends are invited to dance at a feast to celebrate the engagement of Fleur-de-Lys, only to discover that Fleur-de-Lys’s fiancé is none other than her beloved Phoebus. The pas reflects Esmeralda’s heartbreak, but by the end, her love for dancing completely takes over. The La Esmeralda Pas de six has since remained in the ballet repertoire and is often performed at galas, but the version that is widely danced today is Agrippina Vaganova’s revival from her 1935 production of Esmeralda. The original pas de six does not contain a variation for Pierre Gringoire; the traditional male variation danced in the pas de six today is set to music from The Talisman and was added to the pas by Vakhtang Chabukiani ca. 1935.

“La Esmeralda Pas de deux”

Despite its title, the so-called La Esmeralda Pas de deux was not created by Petipa, nor does it have anything at all to do with Perrot’s original full length version of the ballet. It has been widely believed that this pas de deux was created by Petipa in his final 1899 revival, but contrary to popular belief, that is not the case. The music is a pastiche of various pieces by Cesare Pugni and Romualdo Marceno:

- Entrée/Adage – a piece from elsewhere in Pugni’s score for Esmeralda

- Male variation – the music of the scene Reverie in Act 1, scene 2 of Esmeralda, in which Esmeralda spells out the name of her beloved Phoebus with large cut-out letters.

- Female variation – a variation by Romualdo Marenco from his ballet Sieba, or The Sword of Wodan, which premièred at La Scala in 1878.

- Coda – a general dance from Act 2 of The Pharaoh’s Daughter.

The origins of the so-called La Esmeralda Pas de deux are unclear, but the pas de deux was first made famous when it was staged by Nicolas Beriosov for his ill-fated, short-lived 1954 production of Esmeralda for the London Festival Ballet. The only legacy from this ill-fated production was this pas de deux, which was staged by Beriosov in the first act and eventually became a staple of the gala and competition circuit. Somehow, this pas de deux found its way into the repertories of various Russian companies, likely via student performances.

After its initial creation, the so-called La Esmeralda Pas de deux went through several versions throughout the mid to late twenieth century. The most famous and common version that is widely performed today was choreographed by English choreographer Ben Stevenson.

References

[1] Quoted in Jules Perrot: Master of the Romantic Ballet (1984), Dance Books Ltd, p. 92

[2] Ivor Guest, Jules Perrot: Master of the Romantic Ballet (1984), p. 112

Sources

- Marius Petipa, Russian Ballet Master: The Memoirs of Marius Petipa. Translated ed. by Helen Whittaker, introduction and edited by Lillian Moore. London, UK: Dance Books Ltd (1958)

- Anoton Dolin (1966) The Sleeping Ballerina: The Story of Olga Spessivtzeva. UK, London: Frederick Muller Ltd

- Ivor Guest (1977) The Divine Virgina: A Biography of Virginia Zucchi. New York, US: Marcel Dekker, Inc.

- Ivor Guest (1984) Jules Perrot: Master of the Romantic Ballet. London, UK: Dance Books Ltd

- Matilda Kschessinskaya, H.S.H. The Princess Romanovsky-Krassinsky (1960) Dancing in Petersburg: The Memoirs of Mathilde Kschessinska. Alton, Hampshire: Dance Books Ltd

- Nikolai Legat (1939) Ballet Russe: Memoirs of Nikolai Legat. London, UK: Methuen

- Roland John Wiley (2007) A Century of Russian Ballet. Alton, Hampshire, UK: Dance Books Ltd

Photos and images: © Dansmuseet, Stockholm © Большой театр России © Victoria and Albert Museum, London © Государственный академический Мариинский театр © CNCS/Pascal François © Bibliothèque nationale de France © Musée l’Opéra © Colette Masson/Roger-Viollet © АРБ имени А. Я. Вагановой © Михаил Логвинов © Михайловский театр, фотограф Стас Левшин. Партнёры проекта: СПбГБУК «Санкт-Петербургская государственная Театральная библиотека». ФГБОУВО «Академия русского балета имени А. Я. Вагановой» СПбГБУК «Михайловский театр». Михаил Логвинов, фотограф. Martine Kahane.